The Politics of Apocalypse

The Seeds of Revolutionary Eschaton in Emile Zola’s Germinal

Eschaton:

noun

- Theology., the final age and the consummation of history, including the Last Judgment and the defeat of evil, the eternal blessedness of the righteous, and, in some traditions, the creation of a new heaven and earth.

- Dictionary.com

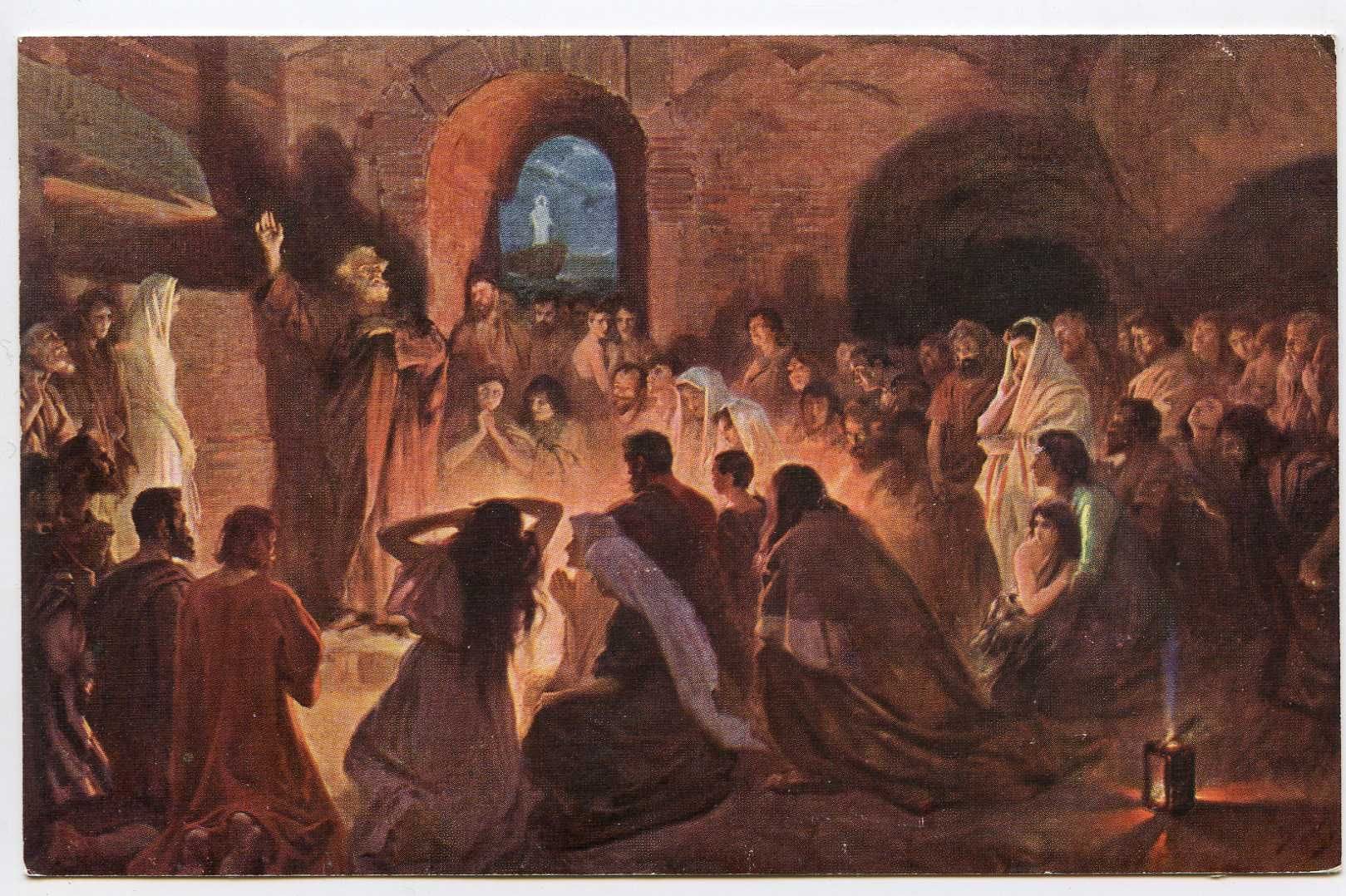

In chapter seven of part four of the novel Germinal by Emile Zola, Etienne, the story’s protagonist, is at the apotheosis of his charismatic, revolutionary status within the mining community of Montsou. Gathered in the forest of Plan-des-Dames, several thousand miners hang on his every word as he exhorts and channels their frustration, pain and desire for justice in a better tomorrow. In this scene, poignantly and uncannily reflecting a religious event, Etienne ‘takes possession’ of the crowd who are ‘like savages, … tracked like wolves’ forced to convene hidden in the forest.

This is not the first time that the imagery of, or indeed word for word, religious symbolism or reference is made in the book. In fact, Zola explicitly refers to the miners in their proto-revolutionary talks and gatherings as analogous to ‘Christians of the early church’. This is because of their ‘fever of hope’ and the sense of impending apocalypse that will bring about a new, dramatically better and heavenly world as the narrative builds towards the strike. Indeed, the book is rife with this type of language and analogy. It would be remiss to not treat the religiosity of Germinal as a major, if not solely predominant, theme of the text.

An uncanny parallel between Etienne at the head of the three thousand miners and another work that is precisely about the early Christians is the novel Quo Vadis? by Henryk Sienkiewicz. In one chapter of Quo Vadis? the young Roman, pagan aristocrat Marcus Vinicius infiltrates a gathering of early Christians in the time of Nero to seek his amor Lygia. The scene is a stark mirror of the one painted by Zola – a clandestine gathering in the woods, torch lit, a crowd of oppressed, suffering peoples of ordinary stock, there to listen about their salvation with fervor and devotion. Only, 2,000 years later, the adherents of Zola’s religion have no god. Theirs is dead, as is mentioned earlier in the book.

This is, as Nietzsche proclaimed, the plight of modernity. God is dead. Yet, Etienne is still a prophet with a flock of sheep. Now however Christ and ‘turning the other cheek’ is no longer sacrosanct. Those eternal promises have been shattered. And in their wake lie the promises of a political ideology. It is Marxism. In this essay we will briefly discuss Marxism in relation to the Christian imagination that so thoroughly permeated Europe after the days of Rome, up until God’s untimely death post-enlightenment and into the industrial revolution.

It bears stating clearly at this juncture in the essay, Christianity was the de facto world view of Europe and all the subsequent branches of the liberal arts and sciences for nearly 2000 years. From architecture to law to science to art, aside from the remains of ‘perennial’ pagan philosophy that was extant in tandem with Christianity’s monopoly on the consciousness of Europe, everything was seen through or referred to the Christian God, Christ and the holy bible.

The historical Christian imagination is critical to our essay for three reasons. One, the sheer depth and length of the Christian worldview left an indelible mark on the European mind as we have already begun to lay out. Two, the death of God is a cataclysmic event that gives rise to our political ideology in question (as well as others) and has direct impact on their operation in the world. And finally three, the Christian imagination in particular relation to the concepts of Utopia and Apocalypse, or Eschaton, are foundational to Marxism, with poignant and highly relevant historical antecedents.

Historical Christian antecedents are critical to the novel Germinal and is foundational to the scene discussed previously. Etienne is a prophet, Zola describes him almost exactly so. After he has given the history of the strike to the crowd in the ‘voice of a secretary of the association.’ in Plan-des-Dames, he then transitions to ‘…the apostle who was bringing truth.’. Zola again and again refers to Etienne and the miners in this explicitly religious terminology, not only in this scene but throughout the novel. This is very important because the gravity of the societal level changes the miners are experiencing, I would argue, can only be dealt with through the language of religion. In turn Marxism, like religion, deals with reality on an equal footing in world-historical terms.

For a bit more context regarding the primacy and development of religious imagination throughout Germinal, the scene in part three, chapter three; Maheude, Etienne and the family discuss their hopes for the future. They deliberately discuss the idea of whether or not God is real. This moment is instructive because it is not merely airy theological discussion. It’s directly operative on their lives and thus their revolutionary activity.

If there is a God, then they will be rewarded in heaven for their sacrifice. They are mollified in their current oppression and obediently live a life of drudgery. Yet if God is not real, then that allows them to feel fresh their oppression and raises the possibility that they may ‘create happiness in this life’. It immediately raises the Utopian dream of ‘each according to his own’. Whether it is a coincidence or not that Zola has these characters mouth the future motto of the Communist party, it is uncanny and singularly important.

The bible is the first source of inspiration for Utopian visions, and indeed it is various Christian writers and sects in the early renaissance to early reformation period that draw directly on biblical inspiration to posit a world where property was shared. And more disconcertingly for the powers that be, that Jesus and his disciples did not own property, and thereby that owning property was immoral and antithetical to true Christianity. As we can see, these are ideas that are directly antecedent to Marx’s, albeit by totally different origins of inquiry into reality.

‘All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had.’ (Acts 4:32)

‘Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.’ (Matthew 19:24)

These verses are relatively straight-forward and unambiguous. And in fact, juxtaposed with the temporal wealth and considerable amount of property owned by the church throughout much of European history, it’s easy to see where there would be conflict. It certainly foreshadows the very same conflict Marx would dedicate his life to elucidating scientifically, as well as the conflict Etienne and his fictional compatriots struggle against throughout Germinal.

Some relevant examples are as follows; four friars of the Franciscan order were burned at the stake in 1318 for taking strict vows of poverty and claiming that Christ and his disciples owned things communally. Many of the Franciscan order were excommunicated and/or executed in this same period for very similar or the same beliefs. Prominent proto-reformation figures like John Wycliffe and Jan Huss challenged church authority, and although in various ways, some salient critiques they shared were a demand for the church to give up it’s worldly possessions based on the previously referenced verses. During the reformation, Thomas Muntzer was an apocalyptic preacher who is held up by Marxists as an early harbinger of ‘bourgeois revolution against feudalism and the struggle for a classless society’ because he extolled the virtues of the peasantry as God’s elect and preached a future, where a totally new society would be theirs.

Indeed, the Reformation is a clear rhyming of the past with our scene and epoch represented in Germinal. In a way, modernity and the death of God is a photo negative of the Reformation’s reimagining of Christianity’s relationship to God. There’s a fundamental shift in man’s relationship with God, which gives forth to a time of revolution and new prophets. Like the proto-Marxist visions of Etienne and the miners of Montsou throughout the book, these Christian reformers and revolutionaries often had a sense that the apocalypse they were living through was the ‘will of God’ and would bring about a new society where God and/or Christ would select the ‘elect’ and guide them in living in perpetuity in harmony. However, as we have already mentioned, there is no God for Etienne and the miners to turn to. So in the gaping spiritual void, they must turn to a burgeoning political ideology that addresses the same themes, but from a totally new perspective.

Following from the above, the theme of the Eschaton and it’s concomitant ushering in of a Utopia, originating from the Christian imagination, is manifest in many Marxist iterations. Marx, in the language of secular ‘dialectical materialism’ predicts very similar themes that grab hold of the imagination of Etienne and the miner’s of Montsou. There will be a time of apocalypse (revolution) that is preordained by God (historical forces of class conflict). After this time of a ‘consummation of history’ the ‘elect’ (proletariat) will be chosen to rule in a new kingdom of heaven (worker’s paradise). There are several other interesting parallels between Christianity and Marxism – the apostles of Christ and the revolutionary vanguard in Leninist-Marxism. The ban on usury between Christians in the bible in medieval Europe and the antipathy Marxism holds towards financial capital. Above all, Marxism, like the apocalyptic mysticism and preaching both in the book of Revelation and among it’s Reformation era forerunners, holds that only a clean break with history is capable of separating the world from it’s sin (production based society).

Overall, I hope to have drawn strong connections between the scene of Etienne preaching and rallying the miner’s of Montsou in the nocturnal woods of Plan-des-Dames and the profound heritage of Christian narrative and symbolism still present in the very same people. In addition, I hope to have shown the broader supporting context through extensive parallels in the Christian imagination and history in mirror image to many fundamental Marxist concepts. In doing so, it seems evident to me that the novel Germinal is emblematic of a singular epoch in history where the masses of Europe, and indeed the world, had to grapple not only with the near total collapse of a millennia old worldview, but also the horrendous reality of exploitative and inhumane working conditions.