The Crucible of Loserdom

Unraveling the Myth of the Glamorous Writer

The lives of great writers I’ve studied are replete with this pattern: a time where they are caste from their Icarian heights into the gutter of insecurity.

It often takes years to work their way into the good graces of the muses, the adoring public and prosperity.

Names such as Hemingway, Camus, Orwell, Goethe, Byron, and Zola would start an incomplete list.

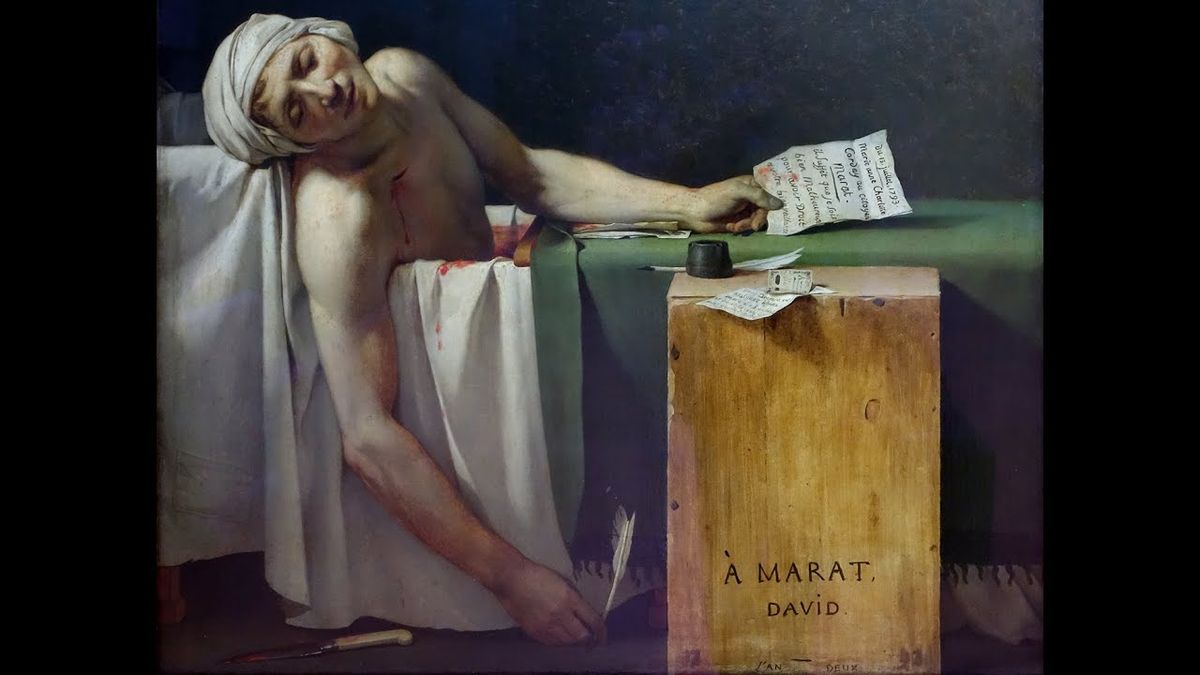

Indeed, many of those cultivated gentlemen instrumental in the French Revolution share similar stories; Jean Paul Marat, Saint-Just, d’Eglantine, Desmoullins and its intellectual forebearer Rousseau.

All these men were in their mid-20’s to mid-30’s, roughly speaking, losers.

These men, without exception, experienced trying times that saw them quite destitute. This seems to be the crucible by which one must pass if one is to achieve the lofty ambitions every successful writer has nursed in his or her breast.

It seems necessary for two reasons:

First, one must spend time honing the craft of writing, learning the business and sifting out one’s talents in concordance with an interesting perspective.

Second, whilst in the midst of becoming a craftsman, the individual who would make the odd decision to become a writer (of all the things one could be), is going through the natural process of mental maturation.

Writers are creatives dedicated to the medium of word and page. No doubt obvious to your very smart brain, dear reader.

For one, success in creative endeavors is associated with being at the high - extreme end of the normal distribution in two of the “Big Five” personality dimensions. That is; trait openness and conscientiousness.

It is also true that modern developmental neuroscience now holds that the prefrontal cortex does not fully develop into maturity until the approximate age of thirty, generally taking longer for men.

How does this seemingly disparate and disconnected data connect to the Crucible of Loserdom for our woe begotten writers, you may ask?

The hypothesis is this: if we assume on average, that the individual who aspire to literary fame is indeed creative then naturally they are likely high in openness on a hypothetical Big Five personality index.

With this assumption, writers at a young age are obviously living with an undeveloped prefrontal cortex that leaves them vulnerable to mistakes inherent to any at this point in life.

This, in turn, would not only make them prone to social isolation but also financial difficulty, as they eschew the well-trodden path society has laid out for them.

Instead, they march to the beat of their muse’s drum, all the way into the gutter.

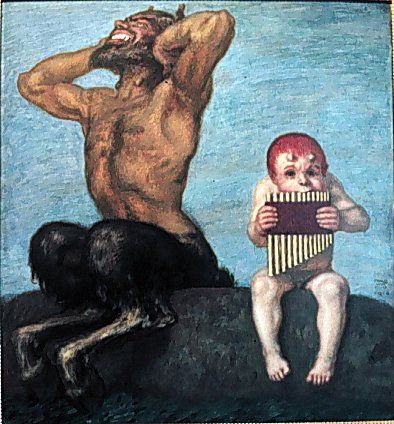

They may seem feckless, moody, bizarre, transgressive, mercurial, delusional, insane to others. Perhaps even themselves.

Indeed, if you study the lives of many great writers, this seems to be the case.

That is; at a certain age their adventurousness and precociousness is no longer as endearing as it had been. They are now another mouth to feed.

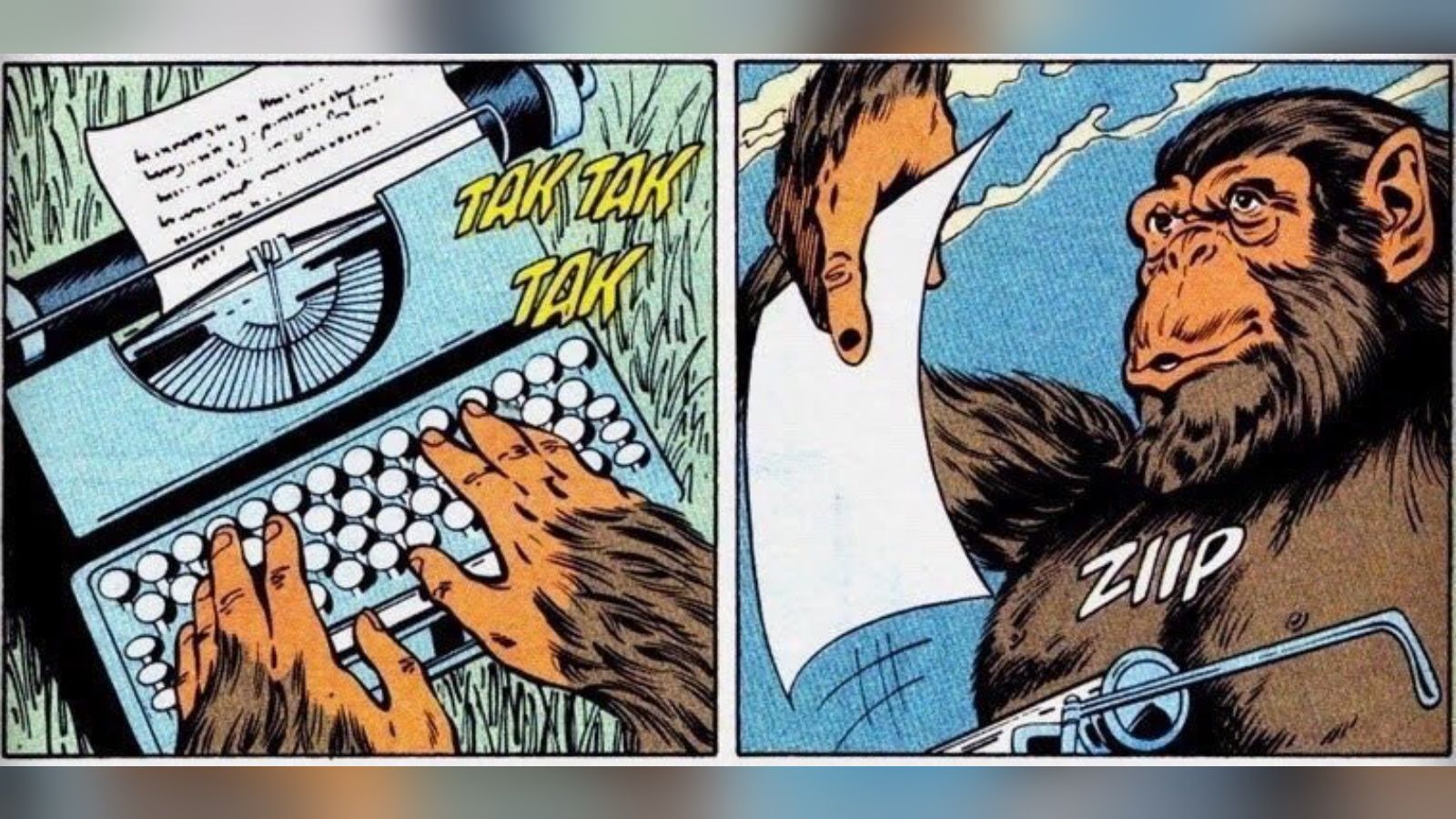

Yet they are entirely preoccupied with writing, that likely at that point in their young lives, isn’t worth a damn.

Now comes the years of honing their craft as well as enduring the humiliation and ostracization of their peers.

In trying to develop an original viewpoint one inherently must separate oneself from conventions that so many blithely mimic.

This is a contentious, confusing, and overwhelming process. Particularly when questioning of norms leads to flouting them.

Then it seems the aspirant is avoiding productive work and the upstanding behavior of prescribed citizenship.

They've become the dreaded bohemian.

This may be a sort of archetypal experience of struggle a writer may go through to become one of stature.

Contrast these rare personality types to the normal distribution of the general population. Add to it a undeveloped brain. Thus, a Crucible of Loserdom.

Now, let us briefly dive into Orwell’s life to examine this dynamic illustrated in one of the 20th centuries greatest authors.

“Every book is a failure.” – George Orwell, Why I Write (1947)

Imagine you emerge exhausted from the medieval bowels of a supposedly high class hotel after a 14 hour shift of washing dishes.

You haven't seen the sunlight, your back aches and your hands are scrubbed raw.

Yet, you and your colleagues are satisfied because you can afford rent in your lice infested boarding room.

You may even splurge on some cheap wine, sausage and sing bawdy songs in a dingy bar for the night.

It is the start of your one day off from the six day work week, after all.

But instead, you go home, lie in bed with your microscopic compatriots and read.

Because destiny is calling you onto something greater.

You are leaving behind the man you once were, to become the man you were born to be.

This was a typical day for a itinerant and unknown Brit living in Paris in the late 1920's.

Eric Blair was born in British colonial India in 1903.

The son of a bureaucrat in the Indian Civil Service (ICS), the colonial administration that governed British India.

He attended school in England from adolescence on, including the prestigious and exclusive Eton college.

He graduated from Eton and immediately afterwards joined the Indian Imperial Police (IIP), where he was stationed in modern Myanmar, then known as Burma.

Now, this is an odd move for young Eric.

He had remarkable filial and academic pedigree in an extremely class conscious society.

Moreover, Eton boasted as alumni eighteen former prime ministers.

Joining the IIP is a bit analogous to any blue blooded aristocrat skipping out on his tour of duty at an Ivy League and the lucrative career on the other end to instead join the Coast Guard.

Like, ok … but why?

Yet so it was.

Over the ensuing five years he served as an assistant district superintendent, where he grew to detest the daily mechanisms of imperialism.

So much so that he resigned from his position in 1927.

These experiences would prompt him to fully abandon all plans of becoming a civil servant; with-it financial stability and social regard in the stringently class-conscious British society.

So now we are at the crux of the issue.

George Orwell is a mere twenty-four years old, turning his back on credibility and security.

He is facing the gaping maw of the world in 1927, based on nothing but principle and a strong desire to write.

Will he be swallowed up by an unforgiving society or will he be able to forge his own path?

He shoves off to what was then the Mecca for all bohemians and artistic wannabes: Paris.

Orwell’s adventures and privations in the city of light are where we can clearly see the course an artist must take in order to chart his own destiny.

In his excellent book, Down and Out in Paris and London, Orwell gives an unflinching account of the underbelly of one of the world’s great seething metropolises.

He details the stark reality of a man with no connections in a city that doesn't give a damn about him; starvation, wretched poverty, lice infected buildings, exhausting drudgery for work, political intrigue, dream crushing false hope, betrayal, uncaring bureaucracy, pawning the clothes off his own back for a meal.

Truly a crucible.

In the context of what it means for a literary aspirant, it is both admirable and horrifying.

This man, once promised so much in the posh halls of the British Empires' civil service, now wallows in the worlds’ receptacles.

Yet, in truly mythological form, he arises from the ashes as a phoenix to become one of the world’s leading lights, likely to be so evermore in posterity.

It took five years of ‘tramping’ to accomplish this harrowing transition.

Even after the initial modest literary success of his early work – Burma Days – the man did not vault into bourgeois comfort.

No, he continued his path of itinerant muck raking, visiting the coal towns of north England in The Road to Wiggin Pier and in the trenches of northern Spain in Homage to Catalonia.

In both works, Orwell goes to the core of world-historical events and comes back with reporting that is fearless chronicling.

From this cache of raw and profound experience, he gave us some of the most laudable and shining works of political fiction the world has known: 1984 and Animal Farm.

Yet was he rewarded for his sacrifices and daring? It’s hard to say.

He certainly gained fame, modest prosperity, and respect in the latter part of his short life, but he lived alone on a small, self-sufficient farm.

He died at the early age of 47 due to tuberculosis.

It’s not unreasonable to guess that succumbing to this disease had something to do with his years of living in wretched conditions.

Yet, his name and work live on as guardians of the values encapsulated broadly in classical liberalism.

Orwell's artistic development is a great example of the neuroscience we explored.

The research vindicates a psychological basis for some reasons as why one would be prone to choosing such an arduous life.

It also gives us insight into the unique difficulties on such a path.

In sum, I hope this removed some veneer for the starry eyed and in turn, gives you impetus to gird your loins for the task you've set yourself.

Be careful what you wish for. Yet do dare to be mighty. You just might do something great along the way.