Leo Tolstoy and the Search for the Modern Soul

How suicidality and nihilism are a backdoor into an earnest search for the soul

Like most things in this life, I am a product of contradictions. Born of an Irish-Catholic mother whose vigorous, unthinking, romantic attachments to her Church’s dogma have caused me turmoil but also great moral and aesthetic feelings. These sentiments collide with the ancestry of my father, a lineage of southern-protestant aristocratic types, of which my grandfather rejected almost whole-cloth in his militant atheism and success in commercial physics. So, I grew up with the quiet coalescing of the two great faiths of the former ages, Christianity and Science, wrestling within me.

Yet internal contradiction of such high degree cannot be sustained for long without some dramatic combustion. For many years I was simply a product of my own contemporary milieu, a pragmatic mix of the old ways and the new, not really thinking too much about either. Yet upon coming to a certain modicum of maturity I found that I could no longer bear the rampant confusion that roiled beneath my daily goings on and felt at core I needed answers for myself, that could enable me to fully live, for I had certainly not been doing that hitherto.

I was plagued by various nascent addictions, insecurities, ignorance, and well-heeled conformism. All of these vectors of dissipation of my daily expenditure of energy led me to a feeling of deep melancholy. Consequently, my life drastically sank into a barely passable simulacrum of participation so as to avoid the responsibility of taking on a great inner feat. I was begrudgingly shoved into trying to solve the problem of my own life. Along the way, I have found some answers.

To even the most casual students of history, it is evident that the story of humanity is written in blood. Despite the incredible spurts of technological innovation achieved as a species in the last two hundred years, which are miraculous, the proclivity for human beings to slaughter each other advanced in tandem. The cult of Logical Positivism, or faith in empirical progress, of the Industrial Revolution and mid-modernity culminated in the dual catastrophes of World War One and two. The rivers of blood spilled across the world were only coagulated by the forming of a political polarity girded by the threat of mutually assured destruction (MAD) via nukes (another outcome of positivism).

However, this essay is not to advance an argument for some type of Luddite ascendency. There is now a strong rise in America and Europe of atavism writ large, a yearning for the reducing of life back into simpler times. Whether it be of a Christian evangelical bent, a Gaia-worshipping, Anthropocene death-cult or as evidenced by the monarchist arguments of Mencius Moldbug and the proliferation of anti-enlightenment Christian nationalism of various sectarian stripes.

These worldviews are gaining ascendency because they generally begin with thorough and salient critiques of the woes of modern culture that are verboten in the current Overton Window, or at least they had been up until recently. With the majority of human history being in accordance with these worldviews, or some other variation of God-King-Society top-down hierarchical structure, these types of ideologies have time and a strong ‘lindy-ness’ on their side. They’re the pillars upon which our humanity is built and so reach into the misty past of our evolutionary hardwiring.

This is perhaps even more remarkable because this is taking place in America and the West given that the exact forms of government that are currently being so deeply challenged come out of the Enlightenment, which sought to control for this very core aspect of humanity. In other words, to control the proclivity to hold onto spiritual-tribal dogma as a core identity. This dramatic gulf in the understanding at the popular and sectarian level of the history of bloodshed that begat the very specific types of governmental structures we have today speaks to the profound effect which said dogmatism resides at the core of the human condition. It is a feature, not a bug.

This doesn’t mean we can, like the Jacobins, create a dogma out of reason and kill off those who hold a different dogma with a more ‘rational’ one. Instead, it begs the question by which every person must live, especially those who are leaders – those who have time and ability to plumb the depths of the perennial issues of humankind – how are we to live?

These issues give rise to search for the modern soul. The universal claim being that with the advent of reason in the public square as the penultimate good we severely damaged our own ability to live in harmony with ourselves and with each other. Not that there was only world peace and good times before, far from it obviously. But we have in large part thrown out the axioms by which Western society lived in the Christian era.

What has occurred in the proceeding time since the enlightenment has been a collective search for how to live, in the words of an exemplary man of the Epoque, Ernst Junger: “It’s a matter of fusing the will to a few formulas from which everything else is drained off.” Previously these formulas were promulgated by the Church. In the interceding years they have been promulgated by science, culminating in the great revelation during COVID that culture is ruled by “The Science” aka Scientism.

This made all too clear what had been quietly talked about for several decades. Even the process by which we humans can sort through the myriad complicated problems that beset our lives on a rational, value-free basis is prone to reverting to tribal unification around a set of catechisms that demands fealty or else enforced punishment.

It is here, in the dissolution of the Neoliberalism, post-enlightenment, and post-Christian eras, that we find ourselves as a species. The previous various worldviews that had persisted through time, by satisfying some aspect of the fundamental needs for humans to be the node that connects from the “spirit” on high (whatever manifestation that may take anthropologically) through the self and then distributed into the social sphere. This gives the individual the sense of well-being and progress that generally produces satisfaction known as happiness. He is in good standing with his God and his peers.

Our current society seems to be lacking a clear and definite answer as to how to go about achieving this sense of harmony that enables man to live. This is primarily evidenced not only by the political drama and rampant psychological maladies that characterize our modern culture but also by the leading cause of death among young people (particularly men) being suicide and addiction. Phrased differently; the youth of our society are experiencing misery so great that they decide to take their own lives. Either slowly or all at once. It’s obvious at this point that at \ core we are experiencing a general spiritual unmooring.

The path on which a solution might be found seems not to be to invent everything new whole cloth. This would be the mistake of communism, as Czeslaw Milosz said in effect, submitting oneself to history begets the realization that history itself is a cruel god. Nor would it be to enslave one to one’s genetics – as the Fascists of the 20th century so fulsomely demonstrated the hellish outcome of that spiritual raison d’etre. Yet still, it is not the case that modern man can renounce his reason, willfully lobotomizing himself so he may return into the fold of the flock a docile sheep once more.

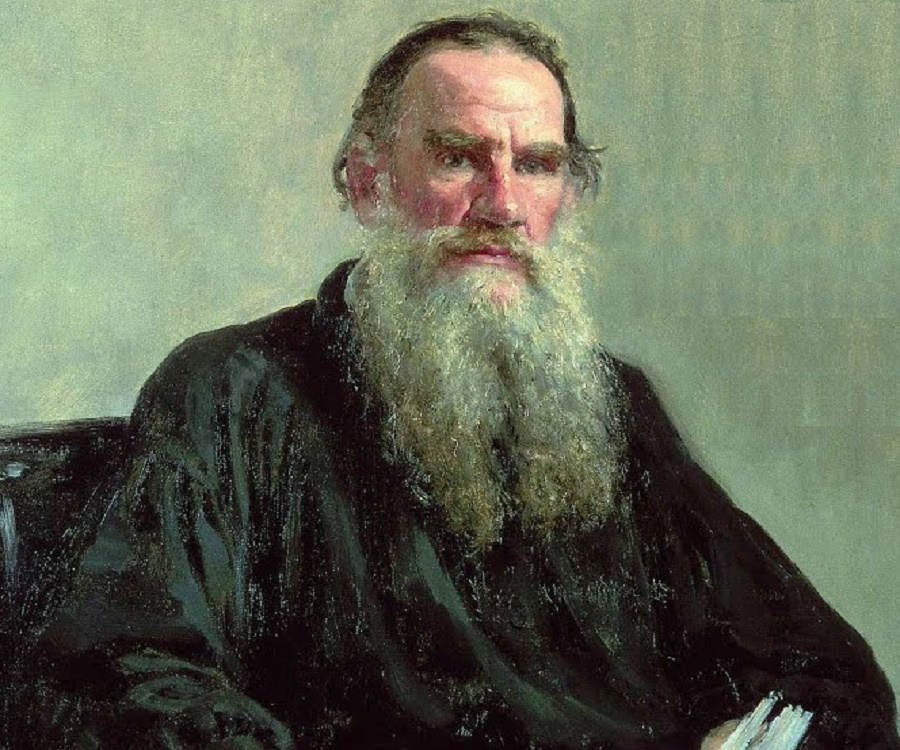

And so, it seems necessary to strive for a harmonious synthesis between faith and reason. It is this journey that has been laid down by many of the great humanists of our species, chief of which is Lev Tolstoy, whose Confession I will walk through in the rest of this essay to explore the path of “Faith” in modernity as he defines in his work as: “The knowledge of the meaning of a man's life, as a result of which a man does not destroy himself but lives.”.

Published in 1882, Tolstoy’s Confession is an utterly remarkable document given its clear and concise explication of the architecture of the modern soul. This man had the temperament of a sage whilst being ensconced in the zeitgeist. He also had the aristocratic leisure to work through over time all the various avenues available to him to pursue meaning in full. What results is a truly amazing document.

In brief, Tolstoy is trying to work out the nagging yet profound reality he finds for himself at the height of his success. It seems that his ascendency to life’s highest realms in his day beget him nothing aside from an acute awareness of the meaninglessness of all things. He writes of the Wisdom he has earned that accumulated to all the great sages – Buddha, Solomon, Socrates and Schopenhauer – life is meaningless and therefore evil. He finds the words of Ecclesiastes to ring true in his own life; that growing in wisdom only grows in sorrow.

Upon coming to this stark realization, he is desperate for a way out. He begins to search for a way to combat the wretched ache in his soul that would have him end his life. He sees at this time, only four categories of ways to abscond from this pain: one is ignorance (already past), two is Epicureanism, three is suicide and four is weakness by which one realizes all this but does not have the strength to carry out the logical conclusion of suicide. A bitter and desperate state indeed.

Yet, his one hope is that he has missed something, that he has made some fatal error. He spends much time retracing what this missed step might be in these humble pages. He finds that his great error was trying to assess the infinite from the view of the finite and vice versa, he begins to see that that is impossible and that rather he should submit himself to the faith of his forefathers – Orthodoxy. And he does so, he becomes deeply ensconced in the traditional catechisms and rites prescribed by the holy church. He does so for many years, humbly submitting himself to every trial and ritual with the attitude that he is wrong and must suppress all desire to argue and disagree.

Yet he finds after many years that he still can not relinquish his reason that so often points out to him the many discrepancies, limitations and natural chauvinism of the various Christian sects. He does come to recognize the limits of his intellect which is a boon, but in so doing sees that it still retains salient when it comes to the epistemology of religion. The various core beliefs he sees practiced and articulated by his church, all ostensibly in the service of the great communal love of the body that is the church, also gives credence to state perpetuated violence – in his day the Russo-Turkish war and the execution of radical political dissidents. His religion cannot hold this simultaneously, as these actions are obviously not born out of love for one’s neighbor and indeed are the antithesis of such a lofty and core tenet.

So, he is once again thrown into the frigid wastelands of being without a community but searching for spiritual succor; ultimate meaning. But he does come across and elucidate a very important truth. Interacting with those at the core of several Christian sects, he finds that they all make the claim that they hold ultimate truth, and though they would pray for their wayward brothers of the other sects, they view them ultimately as heretics and in the grip of some kind of satanic evil. Yet, it is through this prism that each ‘highly-moral true believer’ sees their faith as the ultimate uniting faith. But as Tolstoy so eloquently puts it “And I, who supposed truth lay in the unity of Love, was involuntarily struck by the fact that this very Christian teaching was destroying what it should be producing.”.

Yet he is not one to give up easily and he seeks out all manner of various church fathers (of various sects but predominantly Orthodox), plying them with the following line of questioning; is there not a way that Christianity can be understood at a higher level where all the inconsequential differences would disappear and the faith would shine in unity? Many are sympathetic to his way of thinking. But the answer he ultimately gets is that this union of the churches would be an abandonment of the ancestral way of doing things, eradicating the lineage of Orthodoxy (or Catholicism or Protestantism). And so he realizes:

“If two denominations think they dwell in truth and the other in error, then wanting to bring their brethren to the truth, they will teach their preachings. But if false teachings are preached by simple sons of the church, then this church must burn books and expel the man who leads her sons into temptation.”

And so he comes to the core of a very sad realization. That despite preaching universal love and truth, the churches are caught in temporality and fulfilling human matters in the best way possible but ultimately in a very human way; “…for the fulfillment of human matters one needs force, and it has always been applied, is being applied and will be applied.”.

This is the fundamental issue by which every human institution will fail or succeed. Seemingly aside from small, monastic-like orders of voluntary association whereupon individuals rigorously submit themselves to the total turning over of their sovereignty to a religious system, any large institution concerning the public sphere will primarily draw it’s power and authority from negotiations its relationship between its constituents and force.

Tolstoy concludes his exploration of the whole of church life by acknowledging the grizzly paradox that abuts ultimate brotherly love with the reality of its inherent opposite. It’s a sobering reminder that the clear-eyed walk to true faith, befitting the previous description that also allows for man’s reason to remain intact, is a very difficult road to walk.

“And I paid attention to everything that was being done by people professing Christianity and I was appalled.”

As a tangential note of interest, like Luther, and all great critics that have moved the needle of history, true insight and thereby genuine progress is brought about by a radical commitment to humbly submitting oneself to the institution first to ensure that one is not acting out of one’s own prejudices or character flaws.

But through this all, our dear Lev cannot deny that he has seen the tremendous truth in the traditionally religious life. Millions of simple believers around the world took on life’s burdens with dignity, calm and joy without falling into the pit of nihilism or indulgent epicureanism. So too, as he had adopted the practices of this faith, could he feel the tremendous virtue playing out through his own life. He couldn’t deny the obvious empirical benefits of this faith, this “irrational knowledge” but neither could this rid him of the tension that he was simultaneously living alongside virulent falsehood.

This seems to be the plight of many modern people today that brings about the vicious feeling of flatness to their lives, a diminution of life, caught in between the impossibility of a spiritual void on one side and the rife contradictions of the religious traditions of our planet on the other. We can all sense a deep disenchantment with the status quo, a certain ennui that seeps into every part of our lives, that prods us subtly with the knowledge that we have not fully activated our innate potential. But neither would we wish to end up a communist revolutionary, a raving Dadaist nor a Catholic mendicant as all these roles have historical blood on their hands or present too clearly their foolishness. The rat race of ever-expanding capital has its obvious hollow characteristics and doesn’t succor one at one’s core. And so, the doors quickly shut off for the individual pursuing true faith, a real feeling of being alive attenuated to ethical living, on many fronts.

So what we can learn from our sovereign journeys in pursuit of a righteous faith is that we must live these answers, we must treat our lives as a daily prayer asking what God wants of us in each moment and then doing our best to adhere to that daily anew. We must revere tradition, we must allow its purifying disciplines to melt down our flaws like fire. But we cannot forsake our God-given reason either. We cannot turn a blind eye to the evil and contradictions enacted in the name of brotherly love. So we will undoubtedly face scorn from some true believers drunk on their own self-righteousness. We must simultaneously acknowledge the limits of our intellect whilst accepting its necessity. So to must we accept the cost and responsibility that comes with such humility, “as the necessary consequences of reason.”.

In this way we will lead our own true lives, the one’s God truly intended for us, not the one’s crippled by mindless tradition or fearful conformism. But the only guard against falling into moral turpitude is building off of the universal pillars of human morality not because ‘they said so’ but because they are true and a significant hope we have of living in accord with the truth in the vast mystery of existence. It is a fundamentally challenging, perhaps ineffably paradoxical way of being. The kind of principle only expressed in the lives of the greats or in the same categories of Art, Philosophy and Theology.

Certain that religious teachings hold “..truth and no doubt also falsehood…” he sets himself “the task of separating the one from the other.”. This is the essence of true faith. This is the essence of a life well lived.