How Best to Speak Freely

An exploration of Parrhesia in the court of Alexander the Great

Free Speech is always juxtaposed with violence, whether we realize it or not. Free speech is never truly free. It is tightly correlated with violence when there is a competing set of truths and interests in a given social setting, usually hierarchical.

Hierarchies are how societies distribute wealth and resources. It's how they manage desire. Inevitably many people desire more wealth and resources than there are, and perhaps, they desire more than they truly deserve. There are inevitably objects of desire that are not able to be shared as well. When this occurs, it is called competition. Competition often leads to violence.

The world is violent in many ways, humans are violent, therefor speech is inextricably bound up with violence. Free speech is the best way that humans have evolved to adjudicate the distribution of competitive desires.

The greatest explicator of violence in society, a profound taboo, is Rene Girard. We will first examine the core dynamics of violence in accordance with his theories to frame our exploration into the mechanics of successful free speech.

Mimetic rivalry, as posited by the great Rene Girard, as the bedrock by which all civilizations are dedicated to productively regulating societal violence. Universally, across all time. It is evidenced in the ‘mono-myth’ of the hero’s journey. Not just in the full cycle of the hero’s journey but more specifically in the fundamental conflict the hero must overcome as the progenitor of a given culture.

To marry the two concepts of Joseph Campbell (then great synthesizer of the Hero's Journey) and Girard, the hero is the personification of society writ large. So as to address the core violence that exists underneath daily life. This occurs on an irrational, primal level; emanating from our evolutionary ancestry. These forces are the primary progenitor of violence on a human level. It is the murderous rivalry of Christ & the Pharisees, Cain & Abel, Romulus & Remus, Set & Osirus, Menolaeus & Paris, Hercules & Hector. And so on ad infinitum.

Mimetic rivalry is the great crux of society. The dynamics are of model and imitator. This is the fundamental model of all human political relationships where power is concerned. In the representation of ‘The Hero’, all power and values inherent to the society are contained. The imitator desires the possessions of the model and so, imitates, in order to posses and acquire. There is an object of mutual desire that cannot be shared and so is the progenitor of conflict. And so a violent competition is necessitated.

But as Girard mentions in the most succinct summary of his work, Mimesis and Violence, the object of desire eventually becomes secondary, even unimportant, as the two parties locked in mimetic rivalry become more and more obsessed with each other. The dynamic evolves into the original model imitating the imitator and the imitator thus becoming the modeler. This is the dynamic of the hero come full circle, as through this evolution the imitator is now the true progenitor of the model. The former imitator becomes the modeler and reinvigorates society through his example. Typically this is either a renewal, revelation, or rebirth of certain lost values or new invention of various systems or ideas into ‘history’ as it were from a pre-cosmogenic chaos.

Due to the fact that the vast amount of ‘evidence’ for Mimetic Theory is contained in the anthropological cataloging of foundational myths and not to be found in a lab, it follows that it is a truth to be sussed out not on the level of some incremental insight into the molecular biology of mice synapses, but instead on the level of the great and the universal. This is where we may analyze and compare the substructures of great myths, religions and traditions, thus revealing inductively a basic model that applies universally. In so doing the truth is akin to the religious, or psychological for the modern person. But of a certain branch of psychology, namely, the psychoanalytical truth is revealed.

Therein lies the rub, as this branch of analysis is not of fashion anymore and has several bastardized and confused offspring, and much malady exists thereby. This article is not meant to dissect that problem but this point is relevant insofar as psychoanalysis is perhaps the only branch of science in modernity that still respects ancient means by which humanity predominantly understood and adjudicated societal truths prior to the Cartesian revolution. This is critical because, contrary to the beliefs of the vast majority of modern people, we are still beset and at the mercy of the most primal forces found in human life. Violence, rivalry, sacrifice and death.

This is in the great ‘through line’ of which real progress is made. That is, the improvement by which humans can rationally and justly prevent the condemnation and/or collective murder of innocent victims. In all ways, all times, places and capacities.

This is, in a fundamental sense, the true definition of Justice. As Glaucon says in Plato’s Republic, the most Just man is the one who would be totally innocent, the most good in fact, and yet be the most reviled by the mob. This is also the definition of the scapegoat. The one who society uses to satiate their sociological need to exculpate their own desires for violence. This violence is generated by mimetic rivalry multiplied across the whole of a given society. This in turn is the bleeding heart of all our ‘great’ stories.

It is so because we all experience these dynamics in our lives in one way or another. Great people throughout history have tapped into these energy fields. They tapped into the power of universal archetypes, in Jungian terms, and thereby live out the full cycle of a hero’s journey, complete with the crux of mimetic rivalry and scapegoating, within their lifetimes. Sometimes several times over in one lifetime. This makes them great, definitionaly.

Most mere mortals will typically experience these dynamics in mundane terms and often fragmentary degrees. But the greats, as we have said, experience it in full, time and again. This can be seen and extrapolated upon in any given example of a great person.

But it is seldom to be found so clear and concise as in Plutarch’s life of Alexander. If we take Plutarch’s rendition of Alexander’s life as at least being mostly true and with room for historiographical error, then it is a poignant example of mimetic rivalry and scapegoating in ‘history’. Not only because the dynamics of mimetic rivalry are evident in such vivid and clear terms, but Alexander embodies the various core dynamics both as a rival and as a scapegoat. He lives up to his moniker and experiences these powerful dynamics many times over in his lifetime.

Alexander’s life is also pertinent to dissect through the lens of our line of inquiry because the Greeks lauded Parrhesia, or ‘Frank Speech’. With their various schools of philosophy, many men were wrestling with the challenges of life in clear and virtuous ways. They recorded these encounters for our own edification. They paid attention to the results of living principled, disciplined lives. They couched the study of great men in terms of virtue. So, we have ample data to explore this issue of ‘Frank Speech’ and how best to go about it.

The only vehicle by which humanity has been able to advance society is the artful exercise of free speech. This is the sole pillar upon which justice is able to stand and so, has been the bedrock of all progress hitherto, and mercifully, is the bedrock of the US Constitution.

Unfortunately, as in all periods of increasing mimetic violence, so-called ‘dark ages’, like the one we find ourselves in, speech becomes more contentious and under attack. The rules and understanding of effective Parrhesia are shifting as the ever-evolving arms race of freedom and repression continues on in perpetuity.

Given then, most intelligent people are still ensconced in the institutions that make up our current society where free speech is becoming more difficult, it seems highly relevant and productive to examine in extreme cases how frank speech and violence are navigated. We will examine instances that juxtapose success and failure, sobriety and drunkenness, public speaking and interpersonal discourse. By comparing these opposites we may hope to find beneficial syntheses.

Alexander’s World

First, let us examine Alexander’s speech to the Macedonians after conquering Persia as an example of successful Parrhesia. We will then examine the cases of Cleitus and Callisthenes. Both individuals were killed whilst in Alexander’s retinue. Plutarch does an excellent job of laying out their mistakes and we’ll dissect them further through the lens of Mimetic rivalry.

Now to our first example; Alexander’s Speech to the Macedonians. To summarize (I highly encourage you to read Plutarch’s rendering) Alexander and his army have just totally defeated one of the greatest empires in history with a significantly smaller force than the ones that had amassed against them. The king of Persia, Darius, is dead and Alexander and his army have now inherited his immense, wealthy empire. Alexander is somewhere around the ripe age of 25 and has just pulled off what might seem to be the impossible. And… he wants to do it again.

But there’s just one problem. After several years of campaigning, there are the beginnings of grumblings around the camp. It is time, some say in the Greek army, to go home and see their wives and families. Time to enjoy their much-earned treasure and take a break from the toils and dangers of soldiering.

Alexander is in a tough spot. Having only very recently just conquered this empire, his army may be on the verge of dissolving. It is not inconceivable that these proud and martial Macedonians would make their way back to Greece on their own. It was only a few generations ago that they were warring petty kingdoms and tribes, not united under Philip. What’s more, if Alexander tries to force these men to stay on with him in Asia, he would have to use bloody repression and corporal punishment. This would lead to a great deal of strife and could even backfire, leaving him in the middle of a newly conquered empire with no army. He must negotiate this delicately.

And so he does. The speech recorded by Plutarch is worth dissecting in detail because it is a masterstroke of rhetoric in a precarious situation. The mechanics of it are the real gems to store in your bag next time you may need to rally those around you to a bold course of action.

First, Alexander hears of the spreading desire in the army to return home. What does he do?

Does he panic, become enraged, or cower in his tent distracting himself with pleasures? All things he could have done easily and lesser men may have.

No, instead he waits and eventually decides on a targeted course of action. Knowing the Macedonians are the heart and soul of his army, he places the majority of his army at rest in camp. Then he takes the smaller, core contingent of Macedonians on campaign, where he gathers them to make his speech.

This is critical because if they buy into his plan, the rest of the army will follow. Without them, it disintegrates. This move ensures he does not squander the opportunity to speak to them by holding a gathering en masse, where the weight of numbers could sway these men into doing something against their better interests. He separates them and addresses them directly, his best soldiers.

This is a strong example of the principle of Mimesis at work in real life. The Macedonians, being the crack troops, will be mirrored by the rest of the army. In turn, the Macedonians will mirror Alexander. But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Now, even after these first two wise moves; his poise in facing adversity and his targeted selection of his core followers - he could still face disaster. If he addresses the Macedonians harshly, rebuking them for their disloyalty and presumptuousness, he risks pissing off a very well-trained army. Then he is perhaps in a worse spot if he had let them go. So the stakes are raised by this move to address the issue forthrightly.

He follows up with the judicious and efficacious application of the virtue of Parrhesia. He begins his speech by addressing the danger they are in. Alexander says: “… up to now the barbarians had watched them as if they were in a dream, but if they merely threw the whole country into disorder and retired, the Persians would fall upon them as if they were so many women.”.

He is forthright with his men about the situation. They are in the middle of a freshly conquered empire, enjoying a hot run, but it could all change very quickly. He does not vaunt his personality or invoke the God’s or lament. He gives them the upshot of the need to remain in cohesion and to carry on the campaign to ultimate victory.

For any good general, perhaps even a great general, this would have likely sufficed and the campaign would have commenced in good order. But Alexander is not ‘the Great’ for no reason. Next, is where his mark of genius truly is made. First, he does the astonishing and offers the Macedonians (again, his crack troops) their freedom to leave anyway, despite what he just said about their precarious situation.

This is remarkable for several reasons, but most brilliantly it is because this magnanimity is tremendously unorthodox, contra the long-held military tradition of corporal punishment for desertion.

Then he nails the target home; he merely offers a sportsmanly protest, that when he would try to conquer the world for Macedon he would be abandoned by his men, and only have a small contingent of friends to go with him. He verbally sets them free and only offers regret for what could have been.

Plutarch’s account says the men go wild and begged him to lead them wherever he pleases.

This last bit of rhetoric is genius for two reasons. One, for a man in such a position of power as Alexander to offer these men their freedom despite their disloyalty and a dangerous situation demonstrates greatness. He levels with them men in a way where they’re truly equal. Then, on top of that, to phrase his plan as an offer of the greatest glory imaginable, that he would be remiss in not protesting, shames his men in a way where they cannot do anything else but join him.

Through this speech he has simultaneously touched every part of a man in the decision-making process: reason (the strategic situation), heart (their shame at not accepting his call to adventure), and the soul (his deference to their ultimate freedom, beyond his temporal powers). This speech is, at least in part, an exposition of the critical components of what one must address if one is to persuasively exercise Parrhesia in moments of import that hang in the balance.

To clarify the point even further so we may have a more complete grasp of it, let us examine this virtue from the opposite direction, failures of Parrhesia. Two fantastic episodes in the life of Alexander illustrate the high stakes and necessary deftness needed to successfully exercise Parrhesia. These are the deaths of Cleitus and Callisthenes.

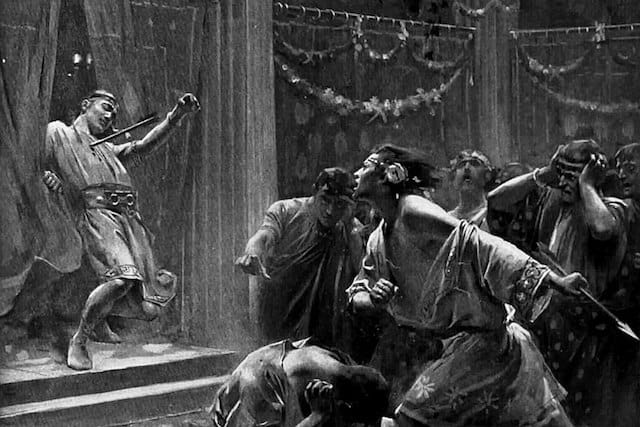

First, Cleitus. Cleitus was a Macedonian nobleman who had already saved Alexander’s life. In the court of conquered Persia, whilst banqueting, a poet lambasted a Macedonian general who had recently been bested by the barbarians (Persians). Cleitus took umbridge pointedly with this remark in front of the whole dinner party being hosted by Alexander. Because of the intoxication of both men, Alexander responded in kind. The contentious question being raised was the bravery of the Macedonians. The poet and the alcohol were merely triggers for deeper currents of doubt and misgivings already rife between Alexander and the Macedonians (as we have already seen).

Ultimately things calmed down for a time, Alexander restored his cool and offered an olive branch to Cleitus, saying the Macedonians were demi-gods among the Greeks. But Cleitus spurned this peace offering, rebuking Alexander and saying it would be better for him to sit at a different table of free men rather than those (Alexander) who worshipped the Persian ways.

At this Alexander was overcome with rage. He grabbed a spear from a guard and impaled Cleitus. It is reported that his rage left him immediately and he was instantly filled with regret. He lamented this incident for days, locking himself away in his tent, weeping in wretched grief. It was only until Anaxarchus (a sophist) came to him and rebuked him, along the lines of shaming him for holding mortal opinion of himself too highly, that he came out of this stupor, all the more autocratic.

Yet, let us remain at the task at hand. How did Cleitus, one of Alexanders' bravest and most loyal, get himself speared to death by the king himself on a banquet floor?

There are several points of erring. First, alcohol seems to be a major negative factor here. However, given it was par for the course in ancient life, it is what it is. That being said, it’s best to keep a level head in your own life and avoid any unnecessary alcohol consumption when addressing matters of delicacy and import.

Second, Cleitus could not take a joke. Though the ancient Macedonians were no doubt a highly proud and martial people, steeped in honor culture, it does not behoove one in a public setting to take these ambiguous affronts as direct challenges. The poet was meant to provide entertainment. Though Cleitus no doubt ‘speaks his mind as a free man’ it is from a place of insecurity, in a very insecure situation, directly needling Alexander where no doubt there was already a sore spot.

That leads to a third error, when speaking frankly, know your audience and their weak points. Cleitus hit Alexander where it hurt, he only cared about his own feelings and could not or did not see that this would gravely incense Alexander. No doubt already feeling that the Macedonians would find his adoption of Persian culture strange in some regard, and knowing they were already longing for home, to raise this so aggressively in company is like trying to build a model ship in a bottle whilst wearing a suit of armor. Or a bull in a china shop. It doesn’t quite fit the situation.

Lastly, Cleitus’s most grievous and fatal error was his scorn of Alexander’s olive branch. We can chalk this up to the alcohol consumption, weariness from the rigors of the campaign and excessive honor-bound pride. Yet all that to say the rebuke is one totally ill-advised. Being in such a dangerous situation, he quite literally spits in the wind. And he gets a spear to the spleen for it.

Frank speech, Parrhesia, is not free. It is not without consequence. It needs to be taken in accord with the gravity that it bears in the world. To shoot from the hip, especially in moments of compromised acuity, is to sometimes risk one's life.

Cleitus, though he was brave and honest, truly and bravely got himself killed by exercising far too much of the afore mentioned virtues and far too little of virtues such as prudence and foresight. A sad shadow cast over Aristotle’s golden mean.

On the other end of the sobriety spectrum, we have Callisthenes. Callisthenes was a philosopher who was schooled in Aristotle’s lyceum and also happened to be the great-nephew of said philosopher. Famously, Alexander had been tutored by Aristotle as a boy, but in recent years had grown cold to the famous lover of Wisdom.

Callisthenes came to Alexander's court in Persia to ‘persuade him to resettle his native city of Olynthus’, a mission I will not feign to know the true nature of. However, Plutarch makes it clear to us that Callisthene's mannerisms, and likely his association with Aristotle, got him into deep waters fairly quickly in Alexander's court.

Callisthenes was a philosopher’s philosopher. Extremely eloquent and intelligent, whilst simultaneously self-effacing and austere. He would reject many invitations to various Bachannate banquets. When he would attend he would sit in ‘morose silence’, clearly communicating his disapproval. He would openly offer rigorous criticism to Alexander and the Macedonians in the middle of court, holding his ground and ruffling feathers without remorse. His most crowning achievement in the adherence to truth despite social pressure was refusing to make obeisance to Alexander in the Persian custom. This was akin to worshipping Alexander as a God and putting Greeks on the same level as Barbarians. Callisthenes was the only one to buck this custom among the Greeks.

Because of these characteristics and behaviors, making him the only one brave enough to stand up to Alexander, he was extremely popular with the youth of the court and also with the ‘oldest and best’ Macedonians. This, in turn, made him very unpopular with Alexander. Callisthenes had a host of other detractors and maligners as well, including Anaxarchus, another prominent philosopher of the court whom we’ve previously met.

We can see that this situation fits exactly the core of Mimetic rivalry. Alexander both men are living, breathing, personifications of great ideals that all other men around them can aspire to. Alexander - the worldly, young, untouchable conqueror. Callisthenes - the staid, traditional, austere philosopher. Both are inhernetly vying for the admiration and leadership of the Greek court in Persia.

Callisthenes has two moments in Plutarch’s rendering that show the bleeding edge of where Parrhesia becomes gambling with your life. After inadvertently denouncing the Macedonians to their faces, and simultaneously antagonizing Alexander at court one day, Callisthenes bows out of the court reciting a very pointed passage from the Iliad: ‘Braver by far than yourself was Patroclus, but death did not spare him.’ several times before he left the hall. Not exactly smoothing things over. And directly underminig Alexander's propaganda and new position as 'God' according to his new Persian crown.

The final straw for Alexander was an attempted coup by one Hermolaus. Hephaestion, Lysimachus and Hagnon (some of Alexander’s best and closest generals) all spread rumors that Callisthenes was proffering himself as the sole light against tyranny in Alexander's camp. When the plot by Hermolaus was discovered, it was mentioned that he had sought out counsel from Callisthenes about how to become the most famous man. Callisthenes's reply was “Kill the most famous man.”. He also was reported to have told Hermolaus not to be overawed by Alexander but that he was a man of flesh, subject to pain and death like all others.

However, these are according to Plutarch, false accusations. Alexander seems to write in letters, and it is also corroborated, that not one of the actual plotters denounced Callisthenes under torture. Even still, Alexander writes that “…as for the sophist, I will punish him myself, and I shall not forget those who sent him to me…”. Clearly, the antipathy Callisthenes had built up for himself with powerful people made it impossible to save him, despite his innocence. He was imprisoned and died shortly thereafter.

He is a useful juxtaposition to our drunken and fiery Cleitus. Totally sober and ascetic, he still did not exercise enough deference to save his own skin. One could argue this is the logical commitment to the principles that he held dear. On the other hand, Aristotle’s golden mean seems to be forgotten here. Although he showed immense fortitude, he exercised courage so boldly that he did so without any finesse. In so doing he did not accomplish the task he set out to do and alienated all those around him, even though there were many who would support and agree with his principles.

It is interesting, that this level of self-effacement, especially in the context of the scapegoating violence that is so prevalent to Girard and the connection with free speech. It does seem to be patently clear, in this case and others, that those who take too hard of a line to exercise their free speech at all costs will eventually pay those costs. On the other hand, sometimes it can work miraculously.

But inevitably if you are going to take on this path, you will face a great deal of scrutiny for you are wandering into the collective unconscious’s storehouse of violence. One becomes a magnet for others to project their own resentful impulses upon. These violent tendencies are always rippling under the surface in any given social context. Especially the nearer one is to the top of hierarchical power structures.

There also seems to be a given threshold of negativity and difference that every social milieu can tolerate a point of tension becomes too great and violence must be expressed. All societies are composed of a spectrum of lies, truth and socially useful lies, as a well as a host of competing possibilities that are seeking dominance.

Alexander, for instance, was seeking to balance the customs and desires of his Macedonians with his new Persian subjects with finesse and accommodation. Callisthenes took a firm line of effort against that. In addition, these tactics may have been more successful if he was more like the king in temperament and attitude. The philosopher's asceticism rivaled too greatly Alexander’s grandeur. So, the scapegoating is triggered along the lines of mimetic rivalries. The rivalry is expressed in dueling lifestyles, between the courtly and the ascetic, and between two cultures, the Greek and the Persian.

Callisthenes was so committed to his principles that he did not steer clear of these rivalries and competitions that existed regardless of his interference or not. And because of this, he became a magnet for all manner of hostility, deserved or not. This is because he was relentlessly uncompromising in his exercise of Parrhesia.

Conclusions

When exercising frank speech, there seem to be some necessary mechanisms of finesse that one needs to adhere to in order to be most efficacious. We saw in both instances where Parrhesia went wrong that the interlocutors were stepping heavily around areas of sensitive matters. We also saw that they were unconcerned with the feelings of their interlocutor and were only able to see their own perspective and the 'righteousness' of it. This is a very tempting and easy trap to fall into, as we all know the satisfaction in being right on a contentious issue.

Yet when we examined Alexander’s speech to the Macedonians we see the contrast to this inability to empathize. Alexander starts with empathy. He starts by pinpointing the pain his troops must feel at being so far from home and offers them what they want, their freedom to return. Then, he does not berate them and demonstrate his superiority by extolling his own virtues, but he almost reluctantly offers them a chance at grandeur, noting his disappointment that they would not share this glory with him. This is where they literally come rushing to his side and demand that he lead them anywhere he saw fit.

Perhaps if Cleitus and Callisthenes had been able to pinpoint Alexander’s pain and find a way to give him what he wanted, they might have also been able to accomplish their ends too. But we have seen the results of their stridency in trying to match force for force with the greatest king on earth at the time.

They are examples of the warning inherent to the wise words of Omar Little; ‘When you come for the king, you best not miss.’