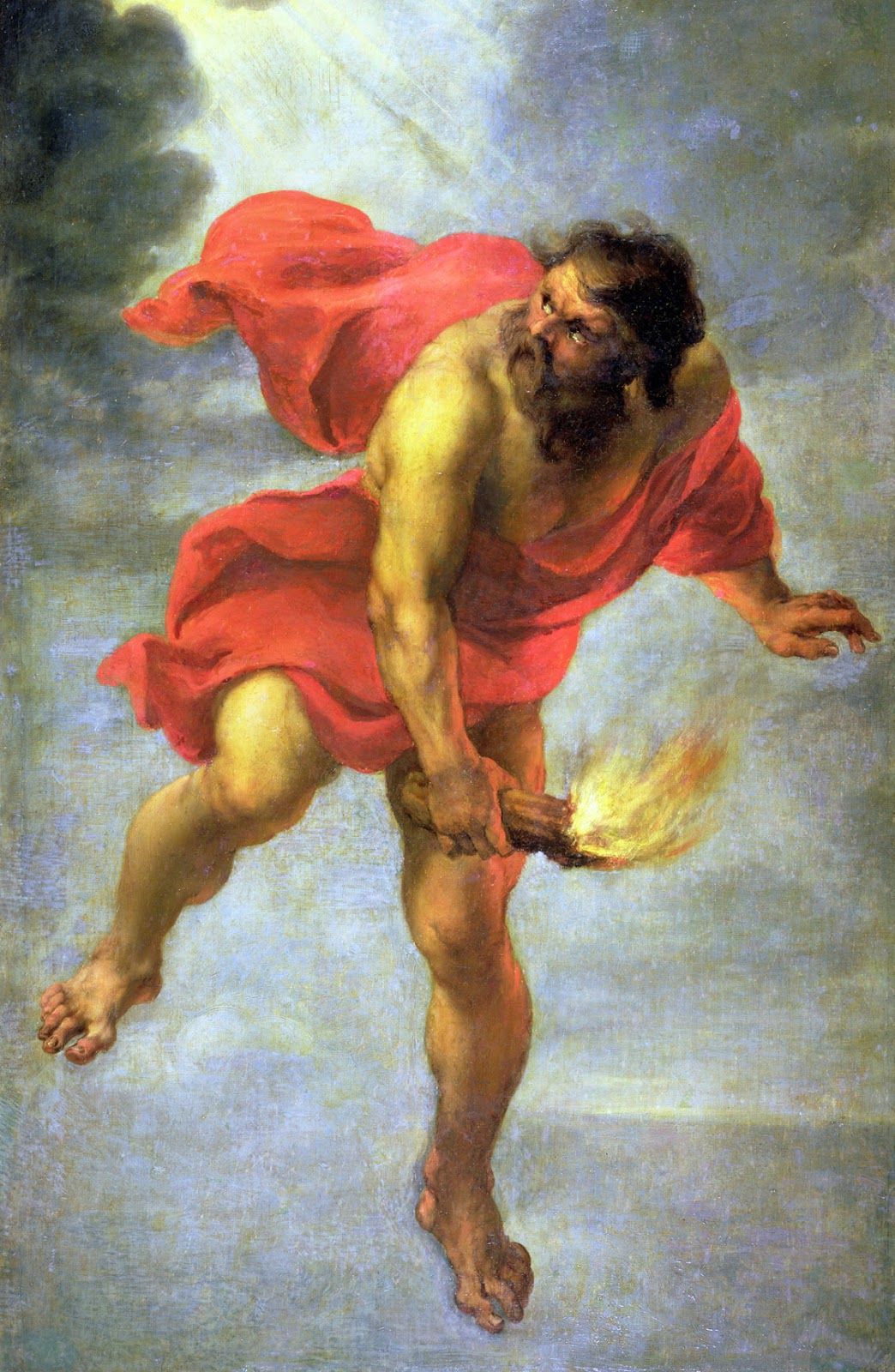

Birth of A Titan

Mapping Emile Zola's Promethean ascent from bohemian to champion of letters & French society

Emile Zola, a titan of his time.

Publishing over three dozen novels (many of which were best-sellers) and hundreds of articles in the leading magazines of France.

Grappling and winning with the gatekeepers of his contemporary military industrial complex and founding an entirely new school of art, all within a lifetime.

Yet, perhaps you've never heard of him.

Or maybe you were forced to slog through Germinal in an undergrad literature class.

But it's this man who charted his course from the gutters of provincial ignominy to becoming a man worthy of renown in his lifetime and study in ours. Particularly for the literary aspirant, yet also any other creator with an independent spirit and voracious drive.

So let us take a look under the hood and examine the mechanics of this great author & journalist's life so that we may distill some lessons in aid of our own quests for triumph, prosperity and satisfaction.

Emile was born the son of an adventurous civil engineer, a former Legionnaire, of mixed Italian-French descent.

His father was the chief architect behind a reservoir and aqueduct system that still provides water to the city of Aix-en-Provence, in the southeast of France.

Sadly, Emile’s father died when he was only seven, leaving his mother and himself in dire poverty. Poverty is the story of Emile’s youth in large part, which in an unsurprising fashion would come to be the focus of many of his later works.

He spent the remainder of his childhood in Aix with his mother and maternal grandmother, where they eked out a living and Emile attended school.

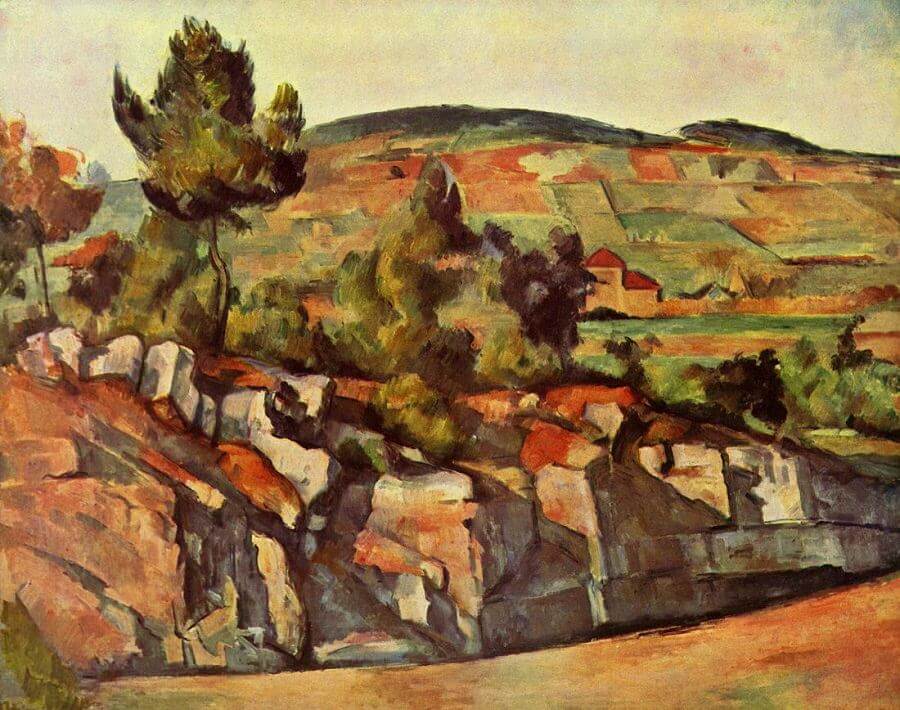

It was later in his youth, still in Provence, that Emile met two of his best friends.

One was Paul Cezanne, the painter of Impressionist renown. The other was a man who shared in his two friends’ artistic ambitions, Louis Baille, but later came to settle in bourgeois comfortability and obscurity.

The three friends spent their teens rambling around the wilderness of Provence, consuming copious amounts of romantic poetry and reciting their own verse.

They all shared the dream of becoming great artists. Yet time waits for no man.

Zola came of age where he needed to support his mother. They moved to Paris in order for young Emile to attain a collegiate degree and thereby a profession.

Unfortunately for Emile at the time, he failed the requisite examinations badly.

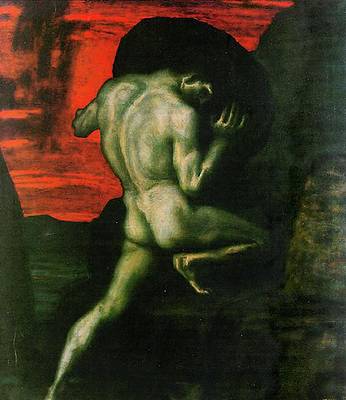

So, it was 1860, Emile was 20 years old, with no profession and still living on his mother, whom only survived off a tiny pension herself.

He was miserable and depressed.

He was still keeping in touch with his friends by letter, Cezanne and Baille, but often to complain of his own weakness.

For two years Zola struggled in this manner.

He spent much of his time wandering around Paris, nearly starving, sleeping in dilapidated housing and even making a “home” with a prostitute.

All the while he was still writing poetry and stories, in Romantic style, popular to the time and the preceding few decades.

He was engrossed with philosophy and literature, constantly reading. He dreamed of great works on the scale of Hugo’s Les Misérables.

Yet his situation did not improve.

He seemed unable to let go of his romantic fantasies of becoming a 'great poet of the age'. He was however, “saved from Bohemia” eventually.

A Parisian doctor who had been a friend of his father procured for him a clerkship at the Hachette Publishing co., then a very prominent one located in Paris.

Here Zola was able to earn a salary that afforded him the daily necessities of keeping body and soul together.

Emile recovered from his wretched destitution in time.

Indeed, he developed a neat and punctilious work ethic as a clerk, undergirded by the stern lessons life had delivered.

As he settled into Hachette he found he was now in the halls of literature he had long dreamed about; interacting with editors, authors and advertisers regularly.

The old flame of ambition was fed further fuel, though now in a more mature form.

He looked around at the people he worked with and saw that they were, in his eyes, merely tradespeople. They did not have the grand vision or talent that he had, in his judgement.

He saw the underbelly of the industry, the social dynamics used in lieu of talent, that so many seemed to leverage to achieve respectability and prosperity.

It was also at Hachette, that as a publicist/liaison, he discovered the immensely important role the newspaper had to play in the success of any given work. In turn he also saw that the economy of the epoch he inhabited hungered for the novel and disdained poetry.

So, finally, he would pick up the form as his own, discarding the lyrical musings of his youth for the hurly-burly world of Parisian magazines and novels.

Now in his mid 20’s, Zola learned to imbue his writing with a Herculean work ethic. After a ten hour workday, he would come home to eat and then lock himself in his room.

He would churn out 1,000 words a day, attempting to always strike consistency. He tried his hand at a novel, of which he wrote 100 pages before ceasing further effort.

It was at this time he also began to find traction with his work in the world. He wrote short stories that were published in various municipally based magazines around France.

He was even politely rejected by Figaro, one of France’s leading journals at the time.

In a time where this was the preeminent artform of entertainment on mass scale, this was a setback, albeit a propitious one.

At this point he had achieved a minimum viable level of prosperity and his persistent writing began coalescing in numerous works of which now he needed to publish to further his ambitions.

Being in the house of power that he was, so near to one of the literary king-makers of the day, Zola was biding his time to submit a work for publication to his boss and owner of the publishing house, Mr. Hachette.

One day Emile did just that.

He snuck into his employer's office during the lunch hour and deposited his manuscript on the desk.

No response came for several days, keeping young Emile in anxiety.

Finally, he was called into the inner sanctum. It did not turn out the way he had hoped it would. He was dressed down for taking the liberty of circumventing the admission process.

However, Mr. Hachette saw in his employee the beginnings of talent; so Zola was actually promoted and given a raise. Further still he was asked to submit a children's story for publication, though it was later rejected.

It is interesting here to note the boldness of action in Zola and how it was rewarded. Though it was not exactly what he wanted, he advanced in significant increment in confidence, metabolizing a valuable experience for further improvement.

His determination, in combination with the development of his prodigious work ethic would come to pay off in due time.

This routine of Zola continued for a few more years, as the young man built up enough momentum writing in the evenings to create the works that would launch his nascent career.

The first is a collection of stories called Contes A Ninon and the second is the Confessions de Claude.

The means by which he managed to publish his first book are instructive. Zola’s obstinate, bullish, confident character manifests again.

He traversed his way through Paris to the then notorious publisher of Left wing literature – Hetzel & Lacroix.

This publishing house was known for printing Hugo, but also pillars of the proto-socialist and anarchist movements and revolutionaries of 1848; such as Lamartine, Proudhon & Fourier.

Zola took his Ninon to the man of the house, after several solicitation attempts at other publishers. He begged, cajoled and asserted his book to be published.

Initially his manuscript was accepted by Lacroix for review, whom promptly forgot about it.

Emile came back many times to the publisher with an imploring, puppy-dog look in his eye. Eventually his persistence won out and his book was published.

A victory for young Emile in his ascent up the literary ladder.

He remarks in a letter to a friend that the battle to get his work published was not as difficult as he had anticipated.

He felt the gust of wind at his back and in turn began to leverage the pullies of the French publishing world in service of his book.

He pleaded for friends to read and review the book. He tapped professional channels via Hachette on company stationary to attain reviews of the work in other publications.

These reviews materialized and along with his next book, Confessions de Claude, he became a minor literary figure.

Hachette, however was a man of the Second Empire and did not like this budding ogre of the Proletariat being housed under his own roof.

Zola saw this inexorable conflict of values as well, and so in 1865, at the age of 24, he resigned from Hachette and took his talents into the market place.

He now had two published books and was a burgeoning man of letters in the center of French cultural life, Paris.

However, he was far from a made man. He had only just begun to find firm footing in a world of big time players.

His early, raw impetus towards being a ‘great poet of the age’ was now morphing into the beginnings of a mature novelist. Indeed, perhaps, a businessman.

Now that he had developed the discipline to become a productive powerhouse, he needed to replace his philosophy of art from the tangential and indulgent whimsies of his romantic youth with something more tangible and real.

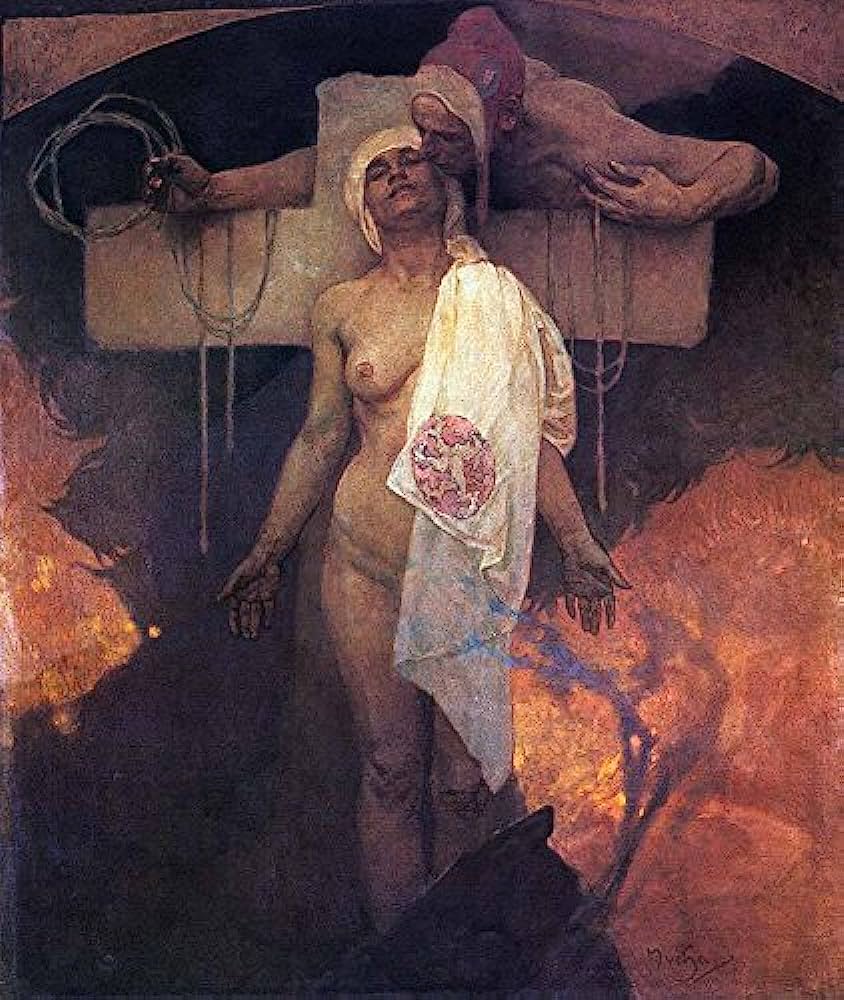

Zola began to grope towards a philosophy of art that would make him a leader of an entirely new school – Naturalism.

It would draw deeply on the large currents of history sweeping France and the whole world at the time; industrialization, poverty, disease, scientific maximalism and myriad other cultural trends.

It would also be for a Zola a means of making sense of his own life, somehow restituting his own pain, struggle and abandonment in former years.

But for us, it is useful enough to see the transformation possible if one put's oneself at the eye of the storm and lays it all on the line.

The moment Emile ceased to be wrapped up in his own arrogance and scorn, his massive internal energies are channeled productively into the domains he long dreamt of conquering.

In these early days we see the growth of the seed into the sapling, and so can in turn trace the roots of the stout and mighty titan Zola would become.

Just so, in any time, place or industry there are dreamers who circle outside the walls of cultural centers; filled with dreams, fantasies and ambitions. Institutional arbiters will always have their foibles and resistance to beneficial change and upstart newcomers.

Yet as we see with Emile, if an aspirant humbles himself to simply go to work day after day within the relevant industry, whilst honing the discipline to perfect their craft patiently over time, then it is eminently possible to make advances rapidly.

So dear reader, how may you apply these lessons to your own situation?

Happy climbing.