Through Every Human Heart

A case study in morality via the life of Ernst Junger

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart – and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good remains.”

- Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

This oft-quoted amalgamation of beautiful, piercing words is to me the center of every human life. It poses to us as humanity (in my very humble opinion) the key question that every person must take on as their cross (if you will) after the apogee of horrors in the 21st century. If one is to truly take on that question as a daily prayer, then one might find great benefit in applying it to “the German problem”. The problem raised in the wake of Germany’s descent into hellish abyss post world-war one. In other words; how could such a refined, educated, ostensibly ‘Liberal’ society (in political form at the time) portend such evil?

There are many levels of analyses one could adopt to answer this question. In this brief article, we take up such a task at the psychological level. We will view it through the window of one human heart. A human heart that is notable and fascinating in the macabre sense because of his cosmic place in history as well as his unique personal attributes. He was, as he put it, “in the belly of Leviathan”. He dissented from the murderous regime. He emerged unscathed, at least physically, when so many others of his ilk did not. He also did not do much in the way that most would warrant morally admirable, though it’s certainly arguable he had the means. He manages, somehow, to sit atop some kind of amoral fence in the midst of one of the most evidently Manichean moments in history. This all being the case, I wager it would do some good to examine this man’s life in some detail.

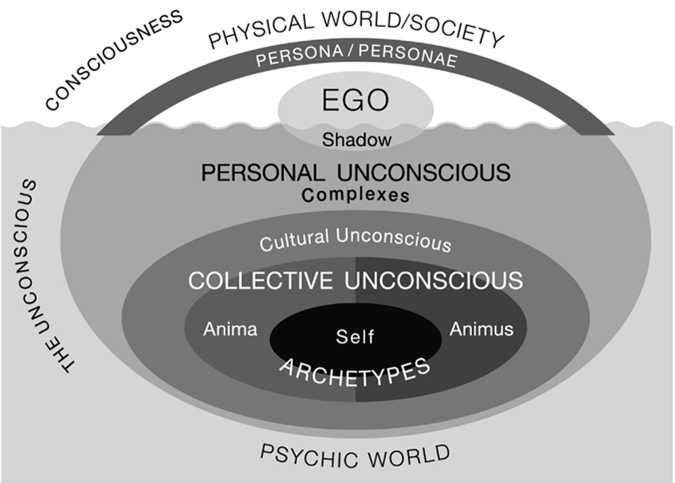

Carl Jung’s theory of the Psyche (the human soul) incorporated a number of concepts that tried to explain the totality of human behavior both on the individual and social levels and the myriad connections between the two. A predominant concept that is instrumental within this framework is called the “Complex”.

A Complex is a subpersonality that can take place on the individual level, idiosyncratic to one person, or it can take place on the societal level (the Collective in Jungian parlance) where it would be qualified as an “Archetypal Complex”.

An archetypal complex is defined as such because it is a distinct ‘personality’ that is universal to humanity, but can be expressed in various permeations; culturally, historically and/or individually.

A simple and relevant example would be the archetypal complex of the “Warrior”. This can be expressed as a Samurai, a Crusader or an American grunt from the Vietnam era. There is a common set of behavior, attitudes, feelings, thoughts, etc. that delineate a “Warrior” in addition to various differentiation given to particular time and place.

A personality complex is one that is exhibited in an individual. It’s origins can be universal, like a “Warrior Complex” or a “Mother Complex”, or they can idiosyncratic. This Jungian concept will be the primary lens of analysis for the psychological dynamics of Junger’s life that I will use.

The information about Junger’s life is garnered almost exclusively from the book: Ernst Junger and Germany: Into the Abyss, 1914-1945. I do not claim to be expert in either Jungian-analysis nor Ernst Junger’s life. So, as I’m sure you’ve already generously concluded in your own heart, please take everything written here as provisional and as edifying fodder for your own meditations.

Magical Beginnings

Ernst Junger was born in Wilhelmine Germany to a zealously rational positivist father and a bohemian, proto-feminist mother; both of whom exemplified the characteristic rebelliousness and ultimate formation of their generation’s zeitgeist. These qualities of Junger’s upbringing seem to be instrumental in his fantastic and charmed life, making them worthy of careful examination.

Young Ernst Junger was raised in a household full of books and devoid of any type of popular conformist system that would shape the world view of his parents. One could fairly say that his childhood was steeped in Romanticism, two very different types of Romanticism, but Romanticism nonetheless.

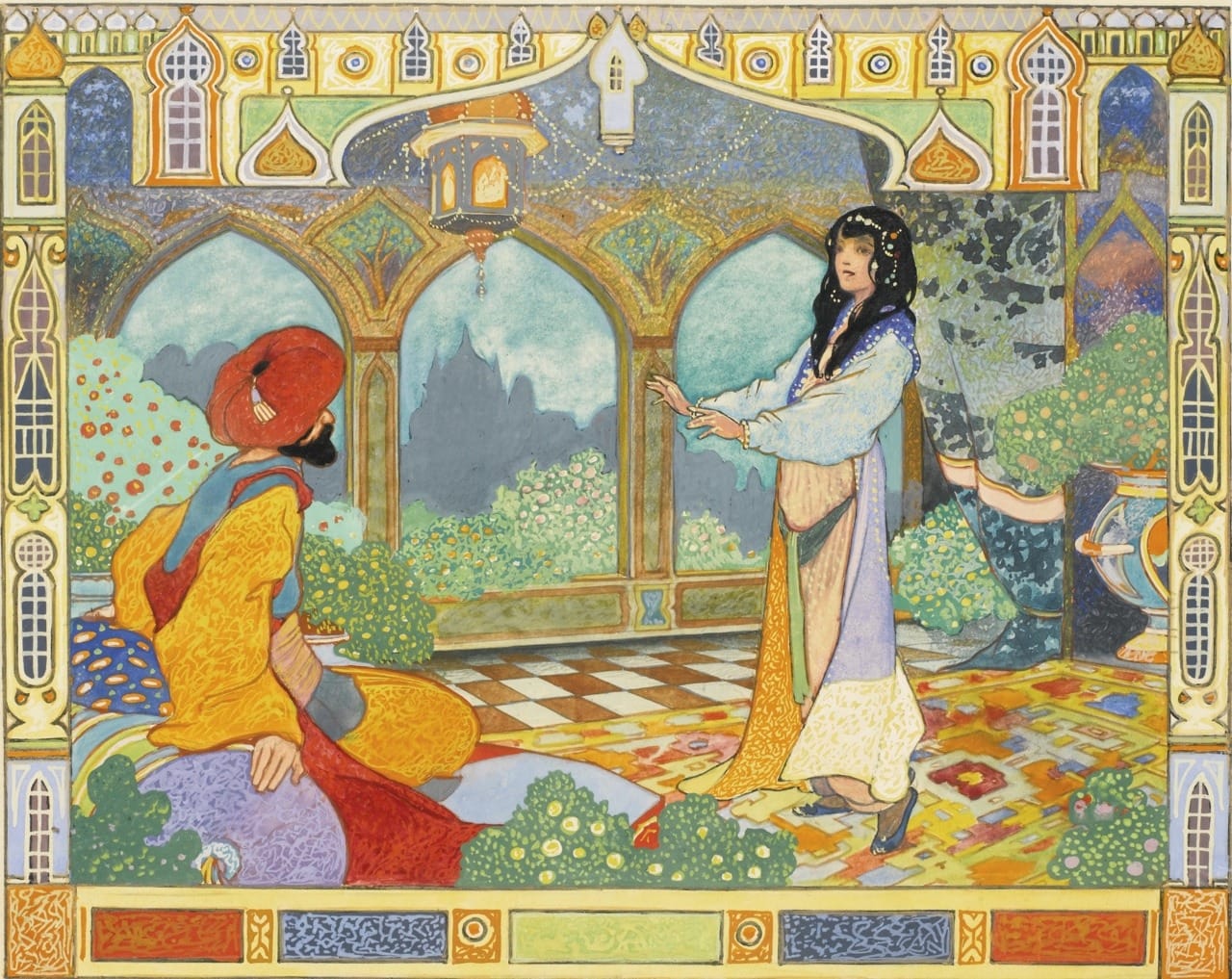

Both his father and his mother were not particularly interested in God and so found the great import of meaning needed in every life from the sources that most drew them, as previously mentioned, a devout positivism in the father and great appreciation for literature in the mother. His father was a successful chemist turned businessman, who would recite the lives of great men such as Alexander and Napoleon to his children at the breakfast table. His mother would read many great works of world-literature to the Junger’s, a favorite of which for young Ernst was Arabian Nights. Another favorite of his childhood was Don Quixote penned by Cervantes.

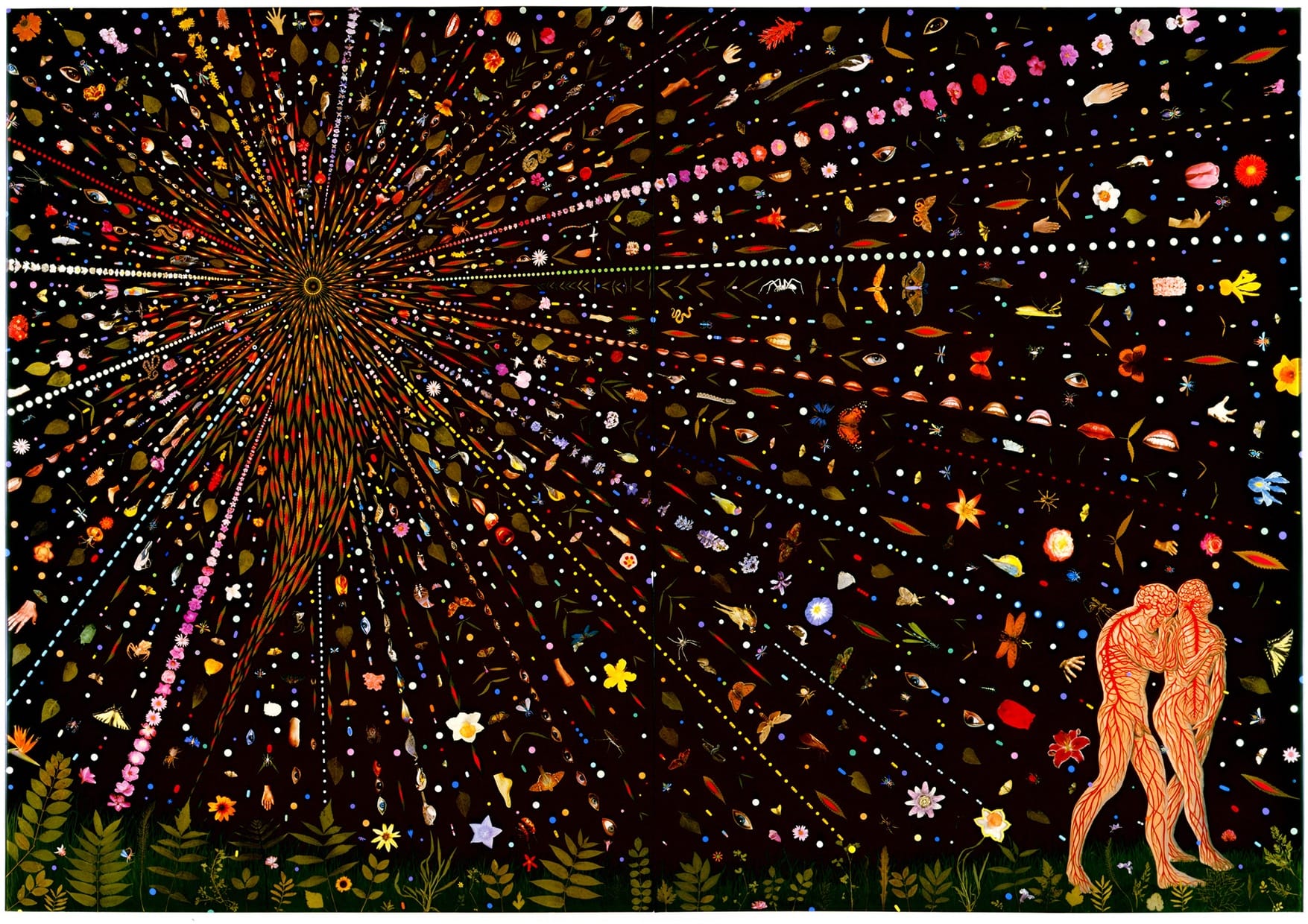

This is where the previous elucidation of Jungian psychology comes into play. If we accept that complexes can come to dominate an individual’s psyche in their lifetime, thereby significantly ruling the course of their lives as akin to a sort of destiny, then it is instructive to examine the chief story that captured young Ernst’s imagination. Jung often used Greek mythology as the basis for understanding and naming complexes, and in this way, if we view the particular tale from the Arabian Nights so influential to Junger as such then it seems we have a potentially explanatory lens by which to view the course of his whole life.

The story comes from Scheherazade, where she tells the tale of three brothers of a certain sultan who are seeking after the heart of their beautiful cousin (such were the times). They are dispatched on a journey to find magical objects, the best of which will be cause for award of their bride. The youngest brother, Ahmad, comes back with an enchanted arrow. All three brothers have magnificent gifts, so the contest is changed to one of strength; whoever can shoot the arrow the farthest wins their bride. They shoot, but Ahmad overshoots his arrow and spends all his time looking for it. So much so that the hand of their cousin is awarded to his second brother.

However, in the midst of his hunt to recover his arrow, Prince Ahmad wanders into the layer of the genie Pari-Banou, a ‘sumptuous grotto’ where he discovers it was she who provided all three magical objects to the brothers. She entices Ahmad to stay with her there, for she is far more beautiful than his cousin. He does so and lives with her for some time.

Yet, as is inevitable in love and parable, all is not well. The sultan eventually learns of his youngest son’s fate and challenges this Jinn to many tests to prove her strength. She passes all with flying colors, culminating in beckoning her ‘fearsome brother’ to kill the sultan and his entire court, setting up Ahmad and herself as the rulers of all India.

Junger loved this story, writing: “…the model of the exalted love-adventure for the sake of which inherited power is gladly renounced. It is beautiful how the young prince in this kingdom disappears as into a more spiritual world.”. Junger wrote these words much later in life, but reading this story as a ten-year-old, it is easy to conceive that it would plant seeds in him that would come to be reaped later in ways that were not possible to foresee then. This is the throughline we shall attempt to trace through his extraordinary life.

Junger’s days in early youth were filled with naturalist tramps around the Hanoverian countryside where he was raised, deeply encouraged by his father’s positivism in a Humboldtian manner. He collected many insects and cataloged them according to Linnaean taxonomy. This is also a very strong influence on Junger’s life. The other side of the coin to his deep literary Romanticism, this notion that empirical observation could and would conquer everything life had to throw at one was the chief animating spirit of his father; as it was for much of the Western mind in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It had no less of a hold on young Ernst.

Ultimately and in brief, his boyhood matured into adolescence through a typical Wilhelmine education at a gymnasium and in a type of German boy scouts. The penultimate adventure of this stage of his life was when he snuck away from his family and in secret joined the French Foreign Legion in hopes of finding the secret to living in the dark continent, Africa. His approximately six-month-long sojourn into North African barracks of the Legion were characterized mostly by his disillusionment with his romantic fantasies (to a degree), his attempted desertion and his father’s eventually successful lobbying with the French government to have his young lad returned to his family on account of “jeunesse foilie” or youthful folly. Quite apt.

All this occurred just in time for Junger to return home for the initial act of the First World War. With a modicum of military training and upon completing his gymnasium studies, he joined the Kaiser’s army in the hope of achieving immortal glory on the battlefield.

War as Aesthetic Catalyst

Junger is perhaps most famous for his memoir of his experiences in the Great War as a stormtrooper commander in Storm of Steel. The book is filled with lyrical expressions of the experience of battles in the modern era, as well as removed, quasi-scientific observations of the anthropology of large armies in the first mechanized, mass, world war. It is, as an aside, entirely worth reading.

But through this recapitulation of his time in war he gained ascendancy as a literary figure in Germany in the early days of the post-war Weimar Republic. He also earned an independent income, despite staying in the army until 1922.

This is the first potential instance of the psychological fruition of the archetypal complex that may have dominated Junger’s life. Like the heroic prince Ahmad, the strength of his attempts at winning at fate so ‘overshoot the mark’, like the proverbial arrow, Junger is propelled into a position at once detached and above the hurly-burly of the Weimar Republic. To nail it down – both his survival as a stormtrooper commander (a feat that is remarkable in itself owing to the high casualty rate of those types of troops) in combination with his literary acumen places him financially and ‘spiritually’ outside the masculine realm of politics. The supernatural, feminine qualities (art via writing) he marries himself to spare him from the turbulent decades to come.

To further evidence this, consider how Junger spends the rest of his days in the ill-fated Weimar Republic. He could have, like Hitler, utilized his war credentials, leadership abilities, and triumph over death to take advantage of the chaos in the incredibly shaky young Republic. Arguably, Junger was perhaps better positioned than Hitler to take power in the vacuum. He was more well-known, more articulate, and had better leadership abilities. He was profoundly anti-democratic as is evidenced by his intermediate career days as a journalist/polemicist/editor. In his writings of the time he called for a dictatorship and was very much involved in the proto-fascist political soup rampant in Germany at the time. But Junger does not do this, although he does court and is courted by the Nazi’s – sending a copy of Storm of Steel to Hitler in 1925 with an admiring inscription referring to him as ‘Fuhrer’ as well as being in the same social milieu of Goebbels in Berlin during the late twenties. Junger also spends much of the mid and early twenties in forays into the aforementioned journalistic sphere, attempting to articulate a vision of some sort of dictatorship that is never exactly clear.

Instead, through his writing in the twenties, he analyzes and aestheticizes his way out of political relevance and viability. His early works are further ‘anthropologies of war’, that although well received, do not advance him in anyway either in the army or political realm. His sojourns in political philosophy culminate over a decade in a tract called The Worker which is at times brilliantly prescient in its analyses of the current technocratic-globalist society beholden to a Nietzschean amorality, yet “conflates myth with metaphysics” akin to Plato’s Republic. He tries to articulate a world vision through literary and symbolic allegory that does not in fact have any constituency, aristocratic or otherwise, and is thereby more a work fantasy than philosophy. The people he envisions that will populate his future dictatorship don’t exist in 1932 and so the work, like much of his political facing writing up until this moment, is rendered inept through its excessive elitism. He also, admirably, publicly repudiates antisemitism in these years.

Thus in combination, Junger was not politically viable by the mid-1930s, as the Nazis had firmly taken control of the country but found no use for the warrior-aesthete. And so, we can see a matching of the storyline from his childhood with the blueprint of his later adult life. His marriage to a life of the mind and art abstracts him from worldly efficacy. Indeed, he would spend the rest of the pre-war years as a professional vacationer, taking long trips without his family to places such as Brazil and Norway, where he could indulge his Humboldtian inclinations and marvel in the vast richness of natural creation whilst writing travel journals. This was a rare opportunity afforded to him by the Third Reich, which was becoming more overtly oppressive as it progressed towards global conflagration. One could argue that this was a welcome distraction from the tides of history for Junger, especially ones so close to home.

An interesting contrast to Junger at this time period is the famous pastor Niemoller, who was also associated with early Nazism’s ascent to power, but ultimately repudiated it and was persecuted, being placed into a prison camp for voicing such opinions. It seems Hitler, oft quoted in the book in various ways as protecting Junger from henchmen who would have the veteran sent to a workcamp, had made up his mind positively about Junger when they had met in 1925 and this had somehow gained Junger immunity from the evil eye of the Third Reich. Junger did not use this immunity or rare freedom of travel to help any of the populations that would be subject to Hitler’s genocidal wrath. He seems not to be aware at all that this is an option.

Later, 1939; the close of the decade and the edge of the precipice for the second world war brings the publication of Junger’s book On the Marble Cliffs, which is stunning on several levels. First, it is one of the only books published by a German author within the Third Reich (a very popular author, mind you) that is dissident to the regime. Second, it is another piece of evidence corroborating our complex theory to a ‘T’.

In it a demagogue “Headhunter” leads a gang of barbarians into a peaceful land. The protagonist and his brother are peaceful men who’ve had their youths consumed by war and so have retired to a life of – that’s right- botany. Wonder where that detail’s inspiration came from? The demagogue ruins the peaceful land and the protagonist, and his brother are merely tourists of the devastation wrought. The apogee of this theme is the final scene where this botanist marvels at the beautiful destruction of civilization below him outside of his laboratory, high up on marble cliffs. This is a remarkable image that will come to pass later in Junger’s waking life in an all too chilling instance of life imitating art. But we shall come to that in due time. For now it is instructive to see that yet again Junger embraces a wholly aestheticizing of his life as a trade-off for having to roll up his sleeves and take risks in the grotesque and manly world of politics.

Witness to Conflagration

With the initiation of World War Two on the European continent, Junger is called up to serve as a Captain with units in the campaign against France that brilliantly execute the blitzkrieg and rapid capitulation of Germany’s timeless foe.

His journals of the period describe his advancement with his unit through the French countryside, aiding civilians in their devastation and protecting cathedrals from destruction. It also carries with it testament to a thread of political discourse that is oft lost to history in textbooks that may be instructive to those deeply considering the “German” problem. Men of Junger’s ilk could in someway view their conquering of Europe and service in the German Wehrmacht within the Third Reich with some degree of virtue because they believed they could unite “Europe” against the hordes of the communist East. There was a possibility of a “spirit of understanding” where France would voluntarily adopt the yoke of Hitler contra Stalin. Or so went the propagandistic line.

Communism at the time was seen as a great scourge not only by followers of Hitler who were at core virulent chauvinists but also the educated, aristocratic elite and their political adherents in the mold of Bismarck. Indeed, Junger writes in his journals with hope about such a possibility in the early years of the French occupation where he was stationed. This “voluntarism” proved to be a minority position throughout France during the occupation, but it was not without its supporters within France and Germany. Ultimately it would become all too clear that the Nazi yoke was one of exploitative evil with deportations, enforced labor and virulent race laws.

In 1940 he is attached to the German Heer (regular army) command of the occupation in Paris, where he would remain for much of the war and write the bulk of his memoirs then. This is yet again proof positive of this man’s fundamental animating complex bearing itself out. In the height of the conflagration, being in the German infantry no less, he is stationed in the city at the center of the art world where he can live off the fat of the land as an occupier. Once again art has abstracted him away from the dirt and blood in the realm of man and he is seated at the center of splendor. There the German army surrenders to “Bacchus and Venus” situated in the city of lights.

He spends the next few years executing his duties (among which once included overseeing an execution of a German soldier), writing, visiting parks and frequenting salons of the artistically inclined left within the city and among German officers. He did not mix well with the artists who allied their talents and prosperity to the fascist regime, to his credit, but he also did not lift a finger to help jews, resistance fights, etc. He was firmly ensconced within the regime.

He found himself among a small group of fellow cultivated, aristocratic officers with whom he could relate. The “cell of knights in the belly of Leviathan.”. They expressly did not proffer each other the zig-heil salute designating their loyalty to Hitler whilst in uniform. In fact, it is from among the ranks of this small cadre that another eerie episode of hyperstition and the only time Junger comes close to taking bonafide action against the evil he was in service to occurs. I will address this shortly along with our other instance of authored destiny from the pages of his novel.

But to cap off his time in service, he is sent to the Eastern front in 1943 for some time. He is a staff officer on the successful campaign in the Caucuses while the rest of the German forces are collapsing on the Eastern front. He witnesses great brutality and almost artistic depravity, as exemplified by the depiction of German soldiers risking their lives volunteering for patrols so they could see the frozen, dead body of a Slavic girl that happened to be naked within their vicinity of operations. He is eventually transferred back to Paris in 1943.

Parisian Hyperstitions

It is in Paris, at the beginning of the waning days of the thousand-year Reich, that truly fascinating instances of hyperstition occur. One has to do with the ‘knights’ whom he associated with, whom he had written about in Marble Cliffs and the second has to do with the axis mundi of Paris itself, also manifesting a quintessential scene from his novel of ‘fantasy’.

A few of the knights that Junger had come to know well were both Erwin Rommel and Hans Speidel. By the early part of mid-1944 they, along with many other German officers, were in major preparations to assassinate Hitler. This was dramatized in the film Operation Valkyrie featuring Tom Cruise. Speidel, a chief of staff in Paris and then for Rommel, was a major architect and a node in the plot. He was the one who forced Junger’s hand, trying to gain a foothold in the last remaining bridgehead of good in the aesthete’s heart.

Junger wrote a political tract (which was later destroyed) that was relayed to Rommel, explicating the need for Germany to restore its Christian values and delineating what that might look like in a post-Hitlerian Reich. It was a treasonous document under the auspices of the current regime. So, in the sole instance of resistance taken by Junger in the war, it was sent to Rommel in May of 1944. According to Speidel, it “deeply impressed” the general.

Junger considered Rommel the modern equivalent of a ‘Sulla” who would be able to lead the rebellion against Hitler from within and secure Germany from ultimate disaster. Unfortunately, the plot was discovered, as history knows. Rommel was forced into suicide. Speidel was arrested by the Gestapo but miraculously was able to escape imprisonment during the last weeks of the war and slip into the safety of the allied armies around Switzerland. It is the final astonishing piece of this event that Junger himself was not arrested, interrogated or tortured at all by the Gestapo for his involvement in the plot. Five thousand other Germans were, including the nation’s best general.

It is this instance that is the first extraordinary example of the fulfillment of his novel. In the book, the resistance fighters against the ‘Head-Hunter’ are noble knights whom the protagonist does not assist but merely watches as they are overwhelmed by the demagogue's might. So it was for his compatriots in real life, some five years later after the books release.

The second instance of literary prophecy is perhaps even more compelling than the previous, though this is a tremendous feat to achieve. During the late summer of 1944, with the Allies having landed in Europe and advancing on the French capital, Junger records in his diary a scene that is astounding in its ahuman detachment. He watches a bombing run on Paris from the roof of his apartment with a bubbly white wine garnished with floating raspberries. He remarks in his alien removal from reality about the beauty of the explosions and the might of the bombs. The apogee of bathos synthesizing with an uncanny ability to bring art into the real world. Just like his protagonist watching the destruction of the beautiful lands below him from the marble cliffs in the works of his pen.

Conclusions

As the book title indicates, it only traces Junger’s life through 1945. That is where our exploration will be capped and we will attempt to draw some conclusions from this man’s life.

Perhaps the most extraordinary fact about Junger’s life, in a life filled with improbabilities, is that he escaped arrest, torture and execution for his complicity in the July 20 plot to assassinate Hitler. The author of Abyss makes a fascinating point that I will tease out further that may explain how Junger was able to avoid an ignominious and painful fate. He states that Junger may have won immunity in perpetuity from Hitler in 1925, when he sent some of his books to Hitler with endearing inscriptions. Nevin points out, that like Albert Speer, Junger may have fulfilled a role of “Artist” that the Reichsfuhrer had inherent respect for and necessitated a certain removal from the rigid adherence to Nazi orthodoxy that most of the party members were obliged to.

Extrapolating from this point, it is a persuasive case. Hitler’s first career choice was famously architecture (if only he had been accepted to the academy, where would the world be?). After his failure in this arena, he led an itinerant life, gravitating towards politics. Junger on the other hand, leads an almost mirror image life. Junger is a man who succeeds early on, both in the warrior and artistic molds in ways that Hitler did not. However, given Hitler’s participation in both domains it’s not inconceivable that he would have significant respect for the man who takes on such endeavors and executed them well.

Further still, it is fascinating to examine Hitler and Junger in this mirror dynamic. Junger, the successful artist interested in politics abstracts himself out of efficacy in this realm through a hyper-aestheticized elitism. Hitler, a failed artist interested in politics, fulfills a mutual suicide-pact with the German hoi polloi and mutually are brought to the lowest, worst experiences in history. Success in art lifts the warrior beyond anything plebian or banal into a rarified spiritual plane. Failure in art brings the demagogue in compact joined with the rude masses into hell.

Another avenue of assessing the fundamental moral virtue (or lack thereof) of Ernst Junger are through his views on Christianity. As the world began to crumble around him in the latter half of the war he began to read the bible, for lack of a better term, religiously. Reading everyday, through the continuity of the war, he was able to formulate Germany’s return to “Christian values” in his political tract to Rommel. Yet, he ultimately comes to the conclusion in his journal that he must find God through his path of “knowledge”, as he puts it “proving god to himself through intellect”. Nevin describes this philosophy as the “Egotism of Goethe” that “bears no cross”. Through his intellect he defies the earthly realm. Here again we find the secret blueprint of Junger’s life coming to fruition.

Indeed, it seems that this attitude is merely the apogee of the confluence of two major cultural forces that animated the Germans and many Europeans of the modern era – a vehement logical positivism combined with Nietzsche’s will-to-power. Through this lens we can see the philosophical mechanisms that allowed Junger to abstain from getting his hands dirty, or perhaps more accurately, being nailed to a cross.

Overall then, Junger seems to me to be the penultimate expression of a certain type of man of his age. He had an instinctual yearning for the “medieval disposition” that he admired in French novelists like Bernanos and Bloy. Also evidenced by his protection of French cathedrals during his command, protecting them from plunder and destruction. However, his intellect and Germanic romanticism of the self overall precluded him from bearing his cross. He could not find an ability to have a personal relationship with God and so did not have much of a personal relationship with the tremendous suffering of his age at all. In this sense, it seems clear to me that he was fundamentally some type of NeoPagan, leading his life under the auspices of the great story of Scheherazade, in the incomparably beautiful and sweet yet celestial, almost alien arms of Pari-Banou.

Like so many of his contemporaries, he sought absolution from the self through mass movement. The animating spirits of individualism and positivism would not lose their firm grips, however. In combination, the man was subject throughout his life to this great story. Perhaps subject to an archetype. Is that destiny? Or did he willingly submit to it, rejecting a cross he could have born? I’ll leave that for you to decide, dear reader.